Over the past decade, India’s entertainment industry has undergone a seismic shift thanks to OTT (over-the-top) streaming platforms. Global giants Netflix and Amazon Prime Video launched in India around 2016–2017, bringing with them new formats and unprecedented creative freedom. This “OTT revolution” has transformed the way Hindi-language stories are told, steering Bollywood and Indian web content into bold new directions. In this article, we analyze how Netflix and Amazon Prime have influenced storytelling style, themes, and formats in Hindi cinema and series.

We compare the pre-OTT era of formulaic Bollywood tropes with the diverse, daring narratives now flourishing online. We also look at audience trends, from binge-watching habits to the surge of rural viewers, and changes in industry practices like casting, budgets, and censorship. In addition, we highlight a couple of striking Tamil/Telugu OTT projects that mirror this storytelling shift.

The rise of streaming has not only democratized content but also created a global audience for Indian stories. Netflix’s first Indian original series Sacred Games (2018) and Amazon’s hit Mirzapur (2018) proved that gritty thrillers with local flavor could captivate viewers worldwide. By 2020, India had multiple homegrown OTT hits, and in a historic moment, Netflix’s crime drama Delhi Crime (2019) even won the International Emmy for Best Drama Series.

Streaming platforms enabled narratives and characters that mainstream Bollywood once avoided, from dark crime sagas to stories about mental health, caste, or LGBTQ+ lives. The OTT boom also changed how Indians consume content: entire seasons are devoured in marathon binge-watching sessions, and streaming has penetrated beyond big cities into small towns and villages. Crucially, the “digital” format freed creators from the strict censorship of theaters, allowing more realistic dialogue, violence, and intimacy on screen. In the following sections, we delve deeper into each of these facets of the OTT revolution, backed by data and expert insights.

A still from Netflix’s crime drama Delhi Crime (2019), which was the first Indian series to win an International Emmy Award for Best Drama Series. Shows like Delhi Crime exemplify the OTT era’s gritty realism and global recognition of Indian storytelling.

Contents

- Bollywood Storytelling Before OTT vs. After OTT

- New Themes, Gritty Genres and Diverse Narratives

- You May Also Like to Read

- Changing Audience Behaviors and Viewership Trends

- Industry Shake-Up: Audience Preferences and Production Practices

- Beyond Bollywood: Regional OTT Storytelling (Tamil & Telugu)

- Conclusion

Bollywood Storytelling Before OTT vs. After OTT

Traditional Bollywood storytelling (in films and network TV) was governed by certain formulas and constraints. Big-screen Hindi cinema often stuck to crowd-pleasing tropes: star-crossed romances, family melodrama, slapstick comedy, larger-than-life heroes, and obligatory song-and-dance numbers irrespective of genre. Mainstream films were designed for mass appeal, which meant avoiding controversial topics and ensuring a “U/A” (parental guidance) certificate from the censor board.

Storylines were generally formulaic, a predictable mix of action, romance, comedy, and drama (the classic masala formula). Theatrical run-times hovered around 2.5 hours with an intermission, and endings usually tied up neatly with moral resolution. On television, Hindi serials and soaps were even more constrained: they faced strict censorship and conservative content standards, leading to repetitive family dramas and fantasy sagas that could run for years. In short, before OTT, creative risks were minimal and narrative diversity was limited.

With the advent of Netflix, Amazon Prime, and other OTT outlets, this picture changed dramatically. The table below highlights key differences between the pre-OTT era and the OTT era of Hindi content:

| Aspect | Pre-OTT Bollywood (Films & TV) | OTT-Era Storytelling (Web/Streaming) |

|---|---|---|

| Censorship & Content | Strict censorship by CBFC; minimal profanity, sexuality, or extreme violence. Filmmakers had to self-censor sensitive scenes or dialogue. | Online platforms initially free of CBFC cuts, enabling bolder content, profanity, nudity, graphic violence, if contextually relevant. Greater creative freedom to explore adult themes. |

| Common Themes/Genres | Formulaic plots (romance, melodrama, action) with broad appeal. Social taboos (crime, caste, LGBTQ, mental health) rarely depicted seriously. Plots often escapist or idealized. | Diverse genres flourish: gritty crime thrillers, dark comedies, dystopias, realistic social dramas. Taboos are tackled head-on, stories about caste prejudice, homosexuality, drugs, politics, etc., find space. More true-story adaptations and genre experimentation. |

| Narrative Format | Mostly 2–3 hour self-contained films with linear narratives; TV had endless episodic serials with ads, often dragging storylines. Relied on interval-based storytelling for theaters. | Multi-episode web series with serialized arcs and cliffhangers to encourage binging. Flexibility in episode length and season length. Anthologies and miniseries emerge as new format (e.g. Lust Stories). Storytelling is tighter and more continuous, designed for on-demand viewing rather than weekly tune-ins. |

| Character & Tone | Hero-centric stories with clear good vs. evil delineation. Major stars carried films; supporting roles less developed. Tones stayed light or melodramatic to avoid offending viewers. | Ensemble casts and anti-heroes are common. Characters are more nuanced or morally grey (e.g. gangsters, flawed cops). Writers develop subplots and backstories in depth over many episodes. Tones range from raw and realistic to quirky or noir, matching global storytelling sensibilities. |

| Representation | LGBTQ+ characters or topics like mental illness were largely absent or depicted via stereotypes/comic relief. Caste or religious tensions addressed superficially if at all. | Inclusive storytelling gains ground, e.g. gay and transgender characters portrayed with empathy (Made in Heaven features a gay protagonist; Paava Kadhaigal explores same-sex love and trans identity). Issues like caste violence, sexism, minority rights and mental health are tackled directly in scripts. |

| Casting & Talent | Bankable movie stars dominated casting; new talent struggled in films. TV actors rarely crossed into films. Content was star-driven over story-driven. | New faces and talented character actors get leading roles in OTT originals, winning acclaim. (For instance, Jaideep Ahlawat headlined Amazon’s Paatal Lok; Shefali Shah led Delhi Crime). Meanwhile, film stars also embrace OTT projects (Saif Ali Khan in Sacred Games, Manoj Bajpayee in The Family Man), blurring industry lines. Casting is now about fit and authenticity, not just star power. |

| Audience & Reach | Cinema targeted urban multiplex and rural single-screen audiences alike, often with diluted content to offend none. TV primarily catered to family audiences with broad sensibilities. Global reach of content was limited (mostly diaspora via DVDs/overseas release). | Niche targeting and global reach: OTT platforms can target specific demographics (e.g. youth for edgy thrillers). Shows have no theatrical boundaries – a series can find viewers worldwide via subtitles/dubs. In fact, 20% of Amazon Prime’s Indian original content viewers now come from outside India. With multiple language options, a Hindi show can be watched by a Tamil or American audience easily. |

As the table suggests, streaming platforms effectively expanded the creative canvas for Indian storytellers. A senior Amazon Prime executive summarized it aptly: “India is a land of storytellers but for a long time, because of the formulaic nature of cinema and TV, not all kinds of stories were told. Streaming has democratised that – subjects that were ignored or avoided now have space”. Similarly, the head of Netflix India content noted that Indian viewers were “hungry for different stories and formats,” making India one of Netflix’s fastest-growing markets.

In short, the OTT era shattered many conventions of Bollywood storytelling, unleashing fresh themes, bolder voices, and new formats that were virtually nonexistent before.

New Themes, Gritty Genres and Diverse Narratives

One of the most visible impacts of the OTT revolution is the explosion of new themes and genres in Hindi content. Where pre-OTT Bollywood mostly steered clear of controversial or niche subjects, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video actively courted them. The change was evident from the earliest Indian originals on these platforms:

Gritty Crime Thrillers: Gangs, guns, and gore found a home on streaming like never before. Netflix’s flagship Indian series Sacred Games (2018) opened with a shocking scene, a dog being hurled to its death from a high-rise, followed by gangster Ganesh Gaitonde’s grim monologue on God and faith. The series dove into Mumbai’s underworld, blending violence, corruption, and dark humor. It freely used profanity, nudity, and drugs as dictated by the plot, elements “not seen before” in Indian television.

Yet, Sacred Games was not mindless provocation; it was a complex cop-versus-criminal saga (starring Saif Ali Khan and Nawazuddin Siddiqui) that felt fresh despite the age-old cops-and-gangsters formula. Its success proved Indian audiences were ready for gritty noir. Following on its heels, Amazon Prime’s Mirzapur (2018) became a pop-culture phenomenon with its tale of warring mafia families in small-town Uttar Pradesh.

Mirzapur’s raw portrayal of violence, power and profanity made its characters like Kaleen Bhaiya and Guddu bhaiya household names, especially among younger viewers who lapped up the meme-worthy dialogues.

Realistic Police and Political Dramas: Streaming allowed dramatizations of real events and topical issues that films rarely touched. Netflix’s Delhi Crime (2019) is a prime example, a series that dramatized the infamous 2012 Delhi gang-rape case from the perspective of the police investigation. The show’s unflinching, sensitive treatment of a tough subject earned critical acclaim and, notably, India’s first International Emmy award for Best Drama Series. This kind of procedural realism and social commentary was a far cry from the glamorized police heroes of Bollywood masala films.

Amazon’s Paatal Lok (2020) went a step further by using a noir crime investigation as a prism to examine India’s social fault lines, caste violence, right-wing extremism, media sensationalism, in a no-holds-barred manner. Despite its dark tone, Paatal Lok resonated widely, showing that audiences appreciated hard-hitting, content-driven stories. Political thrillers also found space: Amazon’s Tandav (2021) attempted a desi House of Cards-style series about power and propaganda (though it stirred controversy for its portrayal of religion and had to trim scenes post-release).

Another Amazon title, The Family Man (2019–21), cleverly blended counter-terrorism action with satirical family comedy, presenting a middle-aged spy balancing national duty and middle-class home life. This genre-mash worked brilliantly, and The Family Man became one of India’s most streamed series, appreciated for its writing and relatable lead (Manoj Bajpayee).

Breaking Taboos, LGBTQ+ and Social Issues: Perhaps the most groundbreaking shift has been the inclusion of stories on gender, sexuality, caste and other previously marginalized themes. For instance, Amazon Prime’s Made in Heaven (2019) is ostensibly about two wedding planners in Delhi, but each episode uses Indian wedding scenarios to critique social evils, from dowry and classism to patriarchy. Notably, one of the two lead characters, Karan, is gay; Made in Heaven portrayed his closeted life and the prejudice he faces, including a harrowing scene where he’s arrested under the now-defunct Section 377 law.

You May Also Like to Read

- Bollywood’s Forgotten Decade: The 2000s Films That Were Ahead of Their Time

- The Evolution of Bollywood Lyrics: From Poetic Classics to Viral Hook Lines

Such frank depiction of a gay protagonist’s life was virtually unheard of in mainstream Indian entertainment before. The show was praised as “far more queer and feminist than Bollywood’s usual fare,” tackling modern urban India’s clash of tradition and liberal values. Netflix too ventured into LGBTQ narratives, e.g. Kapoor & Sons (2016) was a film streaming on the platform that featured a gay character sensitively, but an even bolder example is the anthology film Paava Kadhaigal (2020) on Netflix (Tamil, discussed later) which includes a story about a transgender woman’s love and a lesbian relationship, highlighting prejudices around them.

Mental Health, Internal Struggles: OTT dramas have delved into the psyche of characters in ways Bollywood rarely did. Netflix’s Yeh Meri Family and Little Things touched on everyday mental stress and aspirations of urban youth. Amazon’s Breathe (2018) was a psychological thriller about a father’s extreme steps to save his dying son, blurring moral lines and depicting mental turmoil. Even commercial films that premiered on OTT during the pandemic, like Gehraiyaan (2022 on Amazon), explored complex emotional themes like anxiety, infidelity, and the weight of past trauma in a subdued, realistic tone. The freedom of not catering to a “family audience” in a theater meant creators could address these intimate issues without oversimplification.

Slow-Burn Narratives & Experimental Formats: On streaming, storytellers are not constrained to wrap everything in 150 minutes. They can take their time to build worlds and develop characters over multiple episodes or seasons. This has given rise to some acclaimed slow-burn narratives. Netflix’s Sacred Games itself unraveled its mystery across 16 episodes and two seasons, a pacing impossible in a single film. Amazon’s Paatal Lok and Dahaad (2023) similarly use 8–9 episodes to gradually peel layers off a crime story, allowing for atmospheric storytelling more akin to novels. Anthology formats have also gained popularity, something Bollywood tried only sporadically.

Lust Stories (2018 on Netflix) was a path-breaking anthology film where four top directors (including Karan Johar and Anurag Kashyap) each presented a short story about modern-day relationships and female sexuality. One segment famously showed a middle-class Indian woman (played by Kiara Advani) finding sexual fulfillment via a vibrator, a scene that would have been cut by censors or made conservative viewers squirm in cinemas.

On OTT, it not only survived but sparked nationwide conversations on women’s pleasure. Following its success, Netflix released Ghost Stories (horror shorts) and Amazon came with Unpaused (shorts about life in COVID lockdown), proving anthologies can tackle varied themes in a fresh format.

The creative experiments and bold topics that Netflix and Amazon Prime have championed are often contrasted with the old guard of Bollywood. As film critic Baradwaj Rangan noted, the very existence of series like Sacred Games, replete with “no-holds-barred sex scenes…, unabashed use of violence, cuss words and contentious references”, underlines the power of creative freedom in the digital space. Importantly, these elements are not there to shock for shock’s sake; they are woven into richer, more authentic storytelling.

As one reviewer observed, Sacred Games managed to make an “age-old formula (cop vs gangster) feel fresh purely on the basis of its narrative”, with the explicit content never feeling out of context. Similarly, Delhi Crime’s writer-director Richie Mehta attributed its impact to the time taken to humanize both police and victims, a luxury afforded by the series format, something a feature film adaptation of the case couldn’t have done as effectively.

It’s worth noting that the OTT influx didn’t kill traditional Bollywood genres entirely; instead, it pushed them to evolve. Romantic dramas and comedies still exist on streaming but with a twist, for example, Netflix’s Mismatched (2020) is a young-adult rom-com series set in a coding camp, blending teen romance with modern career pressures. Action is present too, but often in web-series form with more grounded treatment (Amazon’s Mumbai Diaries 26/11 mixed hospital drama with action during the 2008 attacks).

Even the quintessential Bollywood musical element found new expression: Amazon’s Bandish Bandits (2020) centered on classical musicians, weaving in songs organically into a web series narrative. The key difference is that OTT allows these stories to target the audiences that appreciate them, without diluting the content for “everyone.”

In summary, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video catalyzed an era where content is truly “king.” Creators who once struggled to fund offbeat ideas found receptive platforms; viewers who craved variety suddenly had a buffet of genres to choose from, dark crime, edgy romance, sci-fi (OK Computer on Hotstar), mythological fiction (Leila on Netflix imagines a dystopian future), and much more. The storytelling rulebook of Bollywood has been rewritten, as evidenced by the staggering variety of successful OTT titles in just a few years.

Changing Audience Behaviors and Viewership Trends

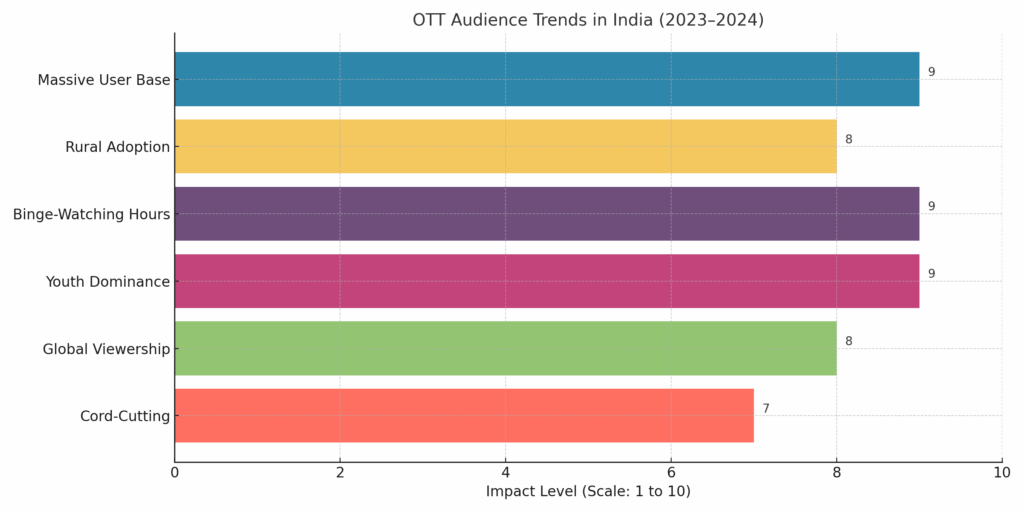

The OTT revolution not only transformed what stories are being told, but also how audiences consume them. Indian viewers have embraced the streaming model with enthusiasm, leading to new patterns of media consumption. Here are some key trends and data points illustrating this shift:

Binge-Watching Culture: With entire seasons at their fingertips, Indians quickly took to binge-watching. In fact, Netflix’s CEO Reed Hastings noted that Indians turned out to be “the fastest binge watchers on Earth,” finishing shows in an average of just 3 days that took global audiences 4+ days. Rather than watching one episode a week, viewers now often devour several in one sitting. A 2022 Amazon report found that Indian households spent more than 4 hours per day streaming content on their smart TVs (via Fire TV devices), a strong indication of the binge trend.

This marks a big change from the pre-OTT days when TV watching was appointment-based and films were a one-off event. Bingeing has also turned many shows into shared cultural experiences, as friends/families race through seasons to avoid spoilers and join the online chatter.

Anywhere, Anytime Viewing: The flexibility of OTT (being able to watch on phone, tablet, laptop, or smart TV) has made content consumption more personal and mobile. A Netflix survey in late-2010s found a huge number of Indians even binge-watch on the go, during commutes or lunch breaks – something practically unheard of with traditional TV. By removing the constraints of broadcast schedules, OTT enabled viewers, especially younger ones, to fit entertainment into their own routine. This also led to the rise of “public bingers,” people comfortable watching shows in public places (trains, cafes) on mobile devices. Essentially, OTT decoupled content from the living room.

Urban and Rural Reach: Perhaps surprisingly, the OTT wave is not limited to India’s metros. Thanks to the cheap mobile data revolution (sparked by Jio’s 4G network in 2016) and widespread smartphone adoption, streaming has penetrated deep into semi-urban and rural India. By 2023, rural internet users actually outnumbered urban users, accounting for about 53% of India’s 820 million active internet users. That means a huge segment of OTT consumers are from smaller towns and villages.

A report by the Internet and Mobile Association of India noted that OTT (video/audio streaming) is one of the top drivers of internet use across demographics, with around 86% of all internet users, roughly 707 million people, using some form of OTT service. This democratization of digital access has eroded the traditional urban bias of premium content. For example, Amazon’s Mirzapur, set in the Hindi heartland, gained massive popularity in small towns, while a quirky rural comedy like Panchayat (on Prime) became a hit even among city viewers, showing content can crossover both ways when distribution is ubiquitous.

Youth Demographics vs. Family Audience: Young Indians have been the vanguard of OTT adoption. Half of India’s population is under 25, and this tech-savvy generation eagerly embraced streaming for its variety and on-demand convenience. As per Statista data, males aged 15–24 formed the largest chunk of Netflix India’s viewership in 2022, reflecting how OTT skewed younger (at least initially). However, the gap is closing as older age groups jump on board. Between 2021 and 2023, there was notable growth in streaming uptake among users aged 35+.

Many middle-aged and senior citizens were introduced to OTT during the Covid-19 lockdowns and found value in its diverse library (from devotional content to classic movies and new originals). Now, one can find entire families sitting together binge-watching a web series, effectively replacing the nightly TV soap opera ritual, but with content of their choosing. The key difference is that OTT allows content segmentation: kids can watch cartoons on Kids profiles while adults watch a crime drama, all on the same platform, personalized to each viewer. This on-demand, personalized consumption is a stark contrast to the one-size-fits-all programming of Indian TV channels.

Viewership Numbers and Global Impact: The scale of OTT viewership in India is striking. Netflix revealed that in 2023, its Indian films and series were watched over 1 billion times on the platform. The most-watched Indian titles on Netflix now rack up tens of millions of views globally within weeks. For instance, a Kareena Kapoor thriller Jaane Jaan (2023) garnered 20.2 million views on Netflix, while the Indian spy thriller series The Night Manager (on Disney+ Hotstar) was among the top trending shows in multiple countries.

Amazon does not publicly share exact numbers often, but it stated that India has been one of its fastest growing Prime Video markets, and importantly, “20% of viewers of [its] Indian original content are now from outside India”. This means Indian OTT stories are finding global audiences, a good example is Delhi Crime, which viewers across the world streamed and which won international awards, or Sacred Games, which had people from the US to Australia hooked (with subtitles). Streaming has essentially broken the distribution barriers, allowing Indian creators to gauge themselves on a world stage.

Cord-Cutting and the Fall of Appointment Viewing: With the rise of streaming, many Indians, especially in urban areas, have reduced or even cancelled their cable/DTH TV subscriptions. They prefer the ad-free, anytime library of OTT apps. A 2024 industry report noted a milestone: for the first time, the number of Indians watching video only via internet (about 208 million) exceeded those watching only via traditional TV (about 181 million). That signals a generational change in content delivery.

Linear TV is no longer the default, streaming is. The same report highlighted that “there are more cord-cutters now, as diversified internet usage leads to new modes of engagement”, and activities like OTT streaming, social media, and gaming are far more democratized across urban-rural divides than activities like online shopping or digital payments. While live sports and news still draw viewers to TV, OTT platforms (including Netflix and Amazon) are now even venturing into sports rights and live events, blurring lines further.

The table below summarizes some of these viewership and audience trends with data:

| OTT Audience Trend | Details & Statistics (India) |

|---|---|

| Massive User Base | OTT video audience in India estimated at 547 million in 2024, ~38% penetration of the population. Growth has been rapid (13–20% annually) but is now driven mostly by ad-supported users as paid subscriber growth slows. |

| Rural Adoption | As of 2023, rural users form 53% of India’s 820M internet users. Thanks to affordable data, OTT content consumption in rural areas now rivals or exceeds that in metros. (One estimate suggests rural India accounts for 65% of OTT content watch-time.) Local language content and Hindi dubbed versions help drive this trend. |

| Binge-Watching Hours | Indian viewers are heavy bingers, an Amazon report found 4+ hours/day spent streaming on connected TVs in 2022. Netflix noted Indians finish series 25% faster than the global average binge pace. Late-night binging has become common, as has multi-episode viewing in one go, affecting even sleep patterns for some (a recent study showed 63% of OTT users have binge-watched until late). |

| Youth Dominance | Youth and young adults lead OTT usage. E.g., 15–24 year-olds were the largest demographic among Netflix India’s viewers in 2022. Platforms also skew towards male users (approx 60% male vs 40% female in 2023) due to historical internet access gaps, though female viewership is rising with more women-oriented content. |

| Global Viewership | Streaming made Indian content global. Amazon Prime’s Indian originals get ~20% of their viewership from overseas audiences. Non-Indian viewers are watching hits like Sacred Games and RRR (picked up by Netflix globally) with subtitles/dubbing. Netflix reported that non-English titles (including Indian) made up nearly one-third of all viewing hours worldwide in late 2023, showing an appetite for Indian stories globally. |

| Cord-Cutting | For the first time, more Indians now watch content via internet-only platforms (208 million) than via traditional TV only (181 million). Many urban households keep just a basic TV connection for sports/news and rely on OTT for entertainment. DTH operators have felt the heat, and some are integrating streaming apps into their set-top boxes to retain customers. |

As these trends indicate, the OTT boom in India is not just a niche urban phenomenon, it’s a nationwide wave that is altering long-entrenched viewing habits. The flexibility, choice, and affordability (many platforms have low-cost plans or ad-based free content) have made OTT accessible to a broad audience. Furthermore, the data-driven approach of platforms helps them cater content to what viewers want, creating a positive feedback loop, for example, if data shows small-town viewers love action thrillers, more such series get greenlit. Audience feedback on social media also directly influences show renewals and cancellations, which is a new dynamic compared to box-office numbers deciding a film’s fate.

However, with great power comes great responsibility – and new challenges. As OTT viewership soared, questions arose about regulation, content quality, and industry impact, which we explore next.

Industry Shake-Up: Audience Preferences and Production Practices

Streaming’s rise forced India’s entertainment industry to adapt in several ways beyond storytelling techniques. Audience preferences have visibly shifted, and in response, industry practices, from casting and budgets to censorship approaches, have evolved.

1. Content Over Stars: One immediate change was that audiences started valuing good content over big star names. In the theatre era, a movie’s opening often depended on the hero’s stardom. But on Netflix/Prime, viewers happily sample a show based on word-of-mouth or interesting trailers, regardless of whether the actors are famous. This led to an outpouring of appreciation for skilled but previously lesser-known actors. For instance, Scam 1992 (on SonyLIV, 2020) made Pratik Gandhi, a regional/Gujarati actor, into a pan-India name for his brilliant portrayal of stockbroker Harshad Mehta.

Jaideep Ahlawat, after years in supporting roles, became a fan-favorite as the dogged cop in Paatal Lok. Shefali Shah, long typecast in minor film roles, earned global accolades as the lead of Delhi Crime. The success of such actors signaled to the industry that talent and fit for the role matter more than star power in the OTT space.

Consequently, casting directors for web series actively scout theater artists, indie film actors, and fresh faces who bring authenticity. This “content is king” trend has started influencing films too, viewers now question poor scripts even if a superstar is in it, because they’ve seen how compelling a series with strong writing (and no superstars) can be. That said, mainstream stars are also jumping onto streaming projects, which further legitimizes the medium.

Saif Ali Khan was among the first Bollywood A-listers to do a web series (Sacred Games), paving the way for others. Soon we saw the likes of Nawazuddin Siddiqui, Abhishek Bachchan, Madhuri Dixit (The Fame Game on Netflix), and even Hrithik Roshan (upcoming War series on OTT) taking up streaming gigs. The audience now doesn’t distinguish much, a quality show is a quality show, be it OTT or film.

2. Bigger Budgets, Bolder Projects: In the initial rush to capture the Indian market, Netflix and Amazon spent lavishly on original productions and content acquisitions. Netflix reportedly invested $400 million in Indian content in just 2019–20, producing over 30 originals in that period. Amazon too pumped in funds for marquee shows (e.g. The Lord of the Rings series dubbed in Indian languages, etc.) and snapped up digital rights of new films.

This inflow of money led to an increase in production quality, better sets, on-location shoots, superior VFX, raising the bar for what audiences expect. A show like Sacred Games had production values comparable to a feature film, and The Forgotten Army (Amazon) staged full-scale war battle scenes for streaming. One side-effect, though, was inflation in talent costs. Top film stars and directors began commanding huge fees for OTT projects too. During the pandemic, when theaters were shut, streaming platforms even bought direct-to-OTT releases of big films at high prices.

Tamil filmmaker Vetrimaaran pointed out that “OTT platforms barged in and gave ₹120 crore for Rajinikanth and Vijay’s films… budgets became bigger [and] actors got used to bigger salaries”, which upset the traditional economics. Essentially, a superstar could get ₹100 crore+ from a streamer for a film’s rights, prompting them to hike their remuneration. While this gave producers options beyond box office, it also made some projects unsustainably expensive.

By 2023, as growth tempered, platforms became more cautious with spending. The early gold rush has cooled – Netflix and Amazon now weigh the ROI on each project carefully, and there’s talk of slightly tighter budgets on Hindi originals after an initial boom. Still, the overall investment in content remains far higher than pre-OTT days, which is why we’re seeing slick, ambitious productions in Hindi and regional languages that we could only dream of before.

3. Creative Freedom vs. Self-Censorship: In the honeymoon phase (2017–2019), OTT creators enjoyed unprecedented freedom from the notorious Indian censorship regime. They could show and say things that TV and films never could, as we’ve discussed. However, this very freedom soon invited scrutiny. As some shows touched political and religious nerves, complaints and FIRs (police cases) were filed. For example, Sacred Games faced a court case because a character cursed a former Prime Minister (Rajiv Gandhi) with an obscene Hindi word.

Leila and Tandav were accused by certain groups of “hurting sentiments” for their dystopian and political themes. Bombay Begums (Netflix) got a notice from the child rights body for showing a teen experimenting with drugs. None of these cases led to bans, but the government took note of the “harmful content” outcry. In late 2020, the Indian government brought OTT platforms under the ambit of the Information & Broadcasting Ministry, effectively signaling that self-regulation must be tightened.

The platforms responded by adopting a self-censorship code, agreeing to content guidelines and grievance redressal. Since 2021, there is a feeling in the creative community that OTT is exercising more caution in greenlighting content that might trigger backlash. Actor Danish Husain observed that an almost “formulaic hackneyed approach” has gripped OTT lately, with everyone churning out crime/espionage stories, “not about audience demand but about self-censorship,” as makers avoid topics that could invite trouble.

He noted that dependence on bankable faces and increased studio interference were creeping in, constricting the creative space once enjoyed. Likewise, filmmaker Anurag Kashyap, who co-created Sacred Games, lamented in 2025 that Netflix and Amazon had become “obsessed with numbers” and were now commissioning safer, “bland content… worse than TV” in a bid not to offend anyone. This critique underscores a current tension: the very platforms that heralded a bold new age are now, due to commercial and political pressures, pulling back on riskier content.

While censorship is still not as heavy-handed as in film/TV (there’s no government body cutting scenes beforehand), a climate of fear and caution has certainly emerged. Many creators now second-guess if their edgy script will actually get approved or asked to tone down. It’s a dynamic situation, the industry is grappling with finding a balance between artistic freedom and avoiding controversies that could invite bans or social media outrage.

As actor Amol Parashar put it, “OTT platforms allow people the freedom to choose what to watch… most viewers are mature enough. Strict censorship isn’t needed on streaming”, arguing that creativity should be protected. The hope among many is that self-regulation will suffice and not stifle the unique voices that OTT brought forth.

4. New Workflow and Talent Ecosystem: OTT’s emphasis on serialized storytelling has elevated the role of writers, showrunners, editors, and cinematographers in the industry. In Bollywood films, directors and stars often overshadowed writers. But a hit series requires strong writing across episodes and often a writers’ room approach (multiple writers collaborating), a relatively new concept in India. Amazon Prime’s content head Aparna Purohit noted that they invested heavily in development by “organising writers’ workshops” and pairing new writers with veteran mentors.

This professionalization is nurturing a generation of screenwriters skilled in long-form narratives. The showrunner concept (chief creative producer of a series) has arrived too, exemplified by Raj & DK who helm Amazon hits like The Family Man and Farzi, overseeing everything from writing to final cut. Additionally, OTT’s production schedules (shooting multiple episodes in one go, often on tighter timelines than films) have made the industry more streamlined and disciplined in some ways.

Top film technicians who earlier did one movie a year are now working on web series in between, increasing the overall content output. The result is a richer talent pool and cross-pollination: film directors like Anurag Kashyap, Zoya Akhtar, Vishal Bhardwaj have directed OTT episodes; OTT directors like Prashant Neel (KGF) or Sujoy Ghosh are getting big projects from streaming. Even technicians, for example, cinematographers who lit up Sacred Games or Made in Heaven brought a cinematic quality that has since influenced how TV serials are shot.

5. Viewer Preferences: Quality and Varietal Tastes: Audiences themselves have evolved in what they demand. Having been exposed to world-class international series on Netflix/Amazon (from Money Heist to Game of Thrones), Indian viewers now expect higher quality writing and production in local content too. This has pushed the industry to up its game. We see far less tolerance for the old clichés among OTT audiences, for instance, viewers on social media will quickly call out a web series if it employs a lazy trope or poor VFX, and negative word-of-mouth can doom a new show.

On the flip side, niche genres have found their fanbases: horror fans finally got Indian horror series (Ghoul, Tumbbad film on Amazon), sci-fi fans got OK Computer, satire lovers got TN3 (TVF’s Panchayat style shows). The ability to cater to micro tastes means creators can take calculated risks knowing there’s an audience segment out there.

Moreover, data analytics helps platforms recommend content, so a user who watches a lot of thrillers will be shown more thrillers, this personalization keeps viewers engaged and shapes their preferences further (sometimes criticized as creating content silos). Binge data also informs storytelling, many series now have a twist or hook at the end of each episode, knowing viewers often auto-play the next one.

In essence, the success of OTT in India has been a learning experience for both creators and consumers. Bollywood and TV industries have learned that audiences will reward originality and authenticity, and that ratings (TRPs) are not the only metric, completion rates, social media trends, and subscriber retention have become the new metrics of success.

The traditional film industry, after some resistance, is also adapting: many studios have now started their own digital arms or tie-ups (e.g., Dharma Productions has Dharmatic for web content, big stars like Akshay Kumar and Ajay Devgn have starred in web series, etc.). There’s also a trend of films being directly released on OTT (especially mid-budget content-driven films that might struggle theatrically). This hybrid model is likely to continue, giving filmmakers more avenues to recoup investments.

Beyond Bollywood: Regional OTT Storytelling (Tamil & Telugu)

The OTT storytelling revolution has not been confined to Hindi-language content. Other regional industries, especially Tamil and Telugu, have also leveraged streaming platforms to tell bolder stories and reach wider audiences. In some cases, they have even set examples that Bollywood later followed. Let’s look at a couple of notable Tamil/Telugu OTT projects that mirror this shift:

“Paava Kadhaigal” (Tamil, 2020, Netflix): This Tamil anthology film (meaning Sinful Tales), directed by four acclaimed filmmakers including Vetri Maaran, Gautham Menon, Sudha Kongara, was one of Netflix’s early regional originals. Paava Kadhaigal shocked many for its intense and realistic portrayal of social taboos. The four short films delve into themes like honor killings, caste-based violence, same-sex love, and the struggles of a transgender person, essentially the darkest “sins” or prejudices plaguing society. One story shows a father (played by Prakash Raj) who cannot overcome caste pride even for his beloved daughter (Sai Pallavi), leading to a tragic honor killing.

Another involves a trans woman’s yearning for love in a conservative village of the 1980s. These are subjects that mainstream Tamil cinema rarely tackled head-on. The anthology does so with unflinching realism, it’s “shockingly realistic” and raises “important questions that linger” after viewing. Critics noted that it never becomes preachy despite handling multiple sensitive issues. The impact of Paava Kadhaigal was significant: it sparked debates in Tamil media about caste crimes and LGBTQ acceptance. For an OTT audience, it was refreshing to see their own regional stars and directors address topics usually brushed under the carpet.

The success of this anthology presumably encouraged similar projects, for example, Netflix later did Navarasa (2021), a Tamil anthology exploring nine emotions, and Amazon commissioned originals like Putham Pudhu Kaalai (Tamil short film collection) and Modern Love Chennai. Paava Kadhaigal showed that the democratizing effect of OTT spans languages, it gave Tamil creators a platform to be as fearless as their Hindi counterparts, and even reach global viewers with subtitles. (Notably, Paava Kadhaigal was among Netflix’s trending content in multiple countries for foreign-language films at the time of its release).

“Pitta Kathalu” (Telugu, 2021 – Netflix): As Netflix’s first Telugu original, Pitta Kathalu was an anthology of four stories directed by different filmmakers, focusing on women protagonists. Titled after the Telugu term for “short stories,” it was essentially the Telugu adaptation of the concept behind Lust Stories. Each segment explored the dark or hidden sides of love and desire, from a political leader manipulating a young couple, to a housewife in an abusive marriage plotting escape.

What stood out was that Pitta Kathalu centered women and did not shy away from showing them as flawed humans rather than idealized figures. “What’s refreshing is we get stories centered on women, and the shorts don’t try to paint them in a positive light. [It] celebrates even flawed women and makes us celebrate their stories,” noted one review. It was bold in theme, though the execution received mixed responses, some segments were praised for originality while others were critiqued for not going far enough.

Nonetheless, Pitta Kathalu was a milestone for Telugu content, traditionally dominated by formula films, proving that Telugu audiences too have an appetite for experimental narratives. It opened the gates for more Telugu web content, for example, Amazon Prime’s Modern Love Hyderabad (2022) or aha (a local OTT) producing series like Kudi Yedamaithe (a sci-fi thriller). Today, you’ll find Telugu crime dramas (SIN, Shootout at Alair) and political dramas (Gangstars) on OTT, which take more risks in storytelling than mainstream Tollywood cinema usually would.

“Suzhal, The Vortex” (Tamil, 2022 – Amazon Prime): This deserves mention as a Tamil web-series that achieved global acclaim. Created by Pushkar–Gayathri (makers of Vikram Vedha), Suzhal is a gripping crime thriller set in a small town in Tamil Nadu. It starts with a teenage girl’s disappearance during a local temple festival, unraveling secrets and social issues as the investigation proceeds. While the premise of a missing person thriller isn’t new, Suzhal stands out for how rooted it is in local culture (the depiction of the Mayana Kollai festival, the use of Tamil folklore) yet how universal its treatment is.

Amazon Prime Video did an unprecedented rollout for Suzhal: it was released worldwide in over 30 languages (subtitles and dubs) simultaneously, including French, Spanish, Korean and more, a first for a Tamil series. This meant a viewer in Brazil or Turkey could discover Suzhal just as easily as one in Chennai. The show earned praise for its atmospheric storytelling and became a case study in how regional Indian content can travel globally if given the platform. Its success has surely encouraged Amazon (and others) to invest more in high-quality Tamil and Telugu originals that can replicate the formula – authentic local stories with world-class production.

In effect, OTT platforms acted as a cultural bridge: Tamil and Telugu content that might never have been accessible to non-local audiences is now one click away for anyone with Netflix or Amazon. This cross-pollination has had some interesting effects. Bollywood is taking inspiration from regional industries’ bold themes, and vice versa. For instance, the hard-hitting Marathi series Samantar or the Malayalam political thriller Pada found new viewers via OTT, proving every language can contribute to the “Indian storytelling” renaissance.

Even more, regional stars gained national/global recognition, The Family Man 2 featured Telugu/Tamil actress Samantha in a pivotal role as a Sri Lankan Tamil rebel, and her performance earned pan-India acclaim (and she’s now doing a Russo Brothers series internationally).

By highlighting regional projects like Paava Kadhaigal or Suzhal, we see that the storytelling shifts, more realism, variety, and taboo topics, are not confined to Hindi/Bollywood. It’s an all-India phenomenon. Each industry retains its flavor (Tamil writers might tackle caste and village honor, Telugu might explore feudal politics, etc.) but the common denominator is pushing the envelope beyond what traditional cinema/TV allowed. In that sense, the OTT revolution is truly a pan-Indian revolution in narrative art.

Conclusion

The arrival of Netflix and Amazon Prime Video in India has unquestionably revolutionized Bollywood and Indian storytelling at large. In just a few years, we have witnessed a content renaissance: narratives that were once deemed too risky or “non-masala” have not only been made, but also loved by audiences. The streaming platforms provided a space for creative experimentation, and Indian creators responded with an outpouring of fresh stories, crime dramas exposing social truths, heartfelt explorations of modern relationships, cutting satires of our politics, and genre-bending thrillers. This bold wave has forced the old guard to evolve as well, raising standards across the board.

As Shibasish Sarkar of Reliance Entertainment observed, “in three years, the cultural side of India achieved on streaming platforms what it would have taken 30 years to achieve in film and TV”. That is a profound statement on how rapid and impactful this change has been.

Of course, the revolution is still a work in progress. As streaming matures, there are challenges: over-saturation (too many shows jostling for attention), the temptation to play safe and chase algorithms (as Kashyap warned), and looming regulatory scrutiny that could curtail the very freedom that made OTT content special. The industry will need to navigate these issues carefully.

Viewers, on their part, will continue to demand authenticity and quality, having gotten a taste of it. The optimistic view is that the gains of this era, the talent breakthroughs, the diversity of content, the global recognition, are irreversible. Even if there is a course-correction toward moderation, Indian storytelling is unlikely to retreat to the naive simplicity of decades past. The audience has evolved, and so have the storytellers.

In the end, the OTT revolution underscores a simple but powerful truth: audiences are ready for good stories, no matter the format, language, or convention. By prioritizing story over spectacle, depth over formula, and inclusivity over one-size-fits-all, Netflix and Amazon Prime Video changed the game. They expanded the definition of “Bollywood storytelling” to include the streets of Mumbai’s crime world, the halls of posh Delhi weddings, the villages of Tamil Nadu, and the psyches of conflicted urban millennials, all coexisting in our content universe.

As India moves forward in this digital storytelling era, one can expect even more boundary-pushing content, possibly interactive shows, cross-cultural collaborations, and a blending of cinema and series formats. The genie is out of the bottle, and it’s telling powerful new tales. For a country long known as “the land of storytelling,” this OTT-fueled creative emancipation is both a revolution and a homecoming, finally, all our stories can find a voice and an audience.