Bollywood song lyrics have undergone a dramatic evolution over the past seven decades. In the early era of Hindi cinema, film songs were revered for their poetic beauty and philosophical depth. Lyricists were often esteemed poets whose verses could stand alone as literature. Fast forward to today, and many Bollywood songs are built around catchy, repetitive “hook lines” engineered to go viral on social media. This article explores this journey, from the Golden Age of soulful poetry to the age of hook-line driven hits, drawing on expert commentary, interviews with legendary lyricists, and analysis of how audiences and technologies have shaped songwriting.

We will compare lyrics across eras (1950s–1970s, 1980s–1990s, 2000s–present) and examine how tone, vocabulary, and artistry have shifted. We’ll also see how today’s lyrics are influenced by Instagram Reels, TikTok (before its ban in India), YouTube Shorts, meme culture, and shorter attention spans. Throughout, we’ll ask: have Bollywood’s lyrics lost their quality or simply evolved with the times?

Contents

- 1950s–1970s: The Golden Age of Poetic and Philosophical Lyrics

- 1980s–1990s: Romantic Ballads, Simpler Language, and the Commercial Turn

- You May Also Like to Read

- 2000s–Present: Mass Appeal, Item Songs, and the Rise of Viral Hook Lines

- The Social Media Effect: TikTok, Reels, and Viral Lyrics

- Changing Audiences, Evolving Art, Loss or Transformation?

1950s–1970s: The Golden Age of Poetic and Philosophical Lyrics

The 1950s to 1970s are often called the Golden Age of Bollywood music, and for good reason. In this period, song lyrics were crafted by renowned poets and writers, resulting in verses of high literary quality. Early Hindi film songs drew heavily from Urdu poetry and literary Hindi. Lyricist Irshad Kamil notes that in the 1940s–50s, Hindi films were “not so as to say Hindi movies” but “heavy on the Urdu side”, since Urdu was widely understood and carried a rich poetic tradition. Many early lyricists, like Sahir Ludhianvi, Shakeel Badayuni, Kaifi Azmi, and Majrooh Sultanpuri, were trained Urdu poets who brought an elegant, refined vocabulary to film songs.

By the 1960s and ’70s, more Hindi literature specialists (like poet Neeraj and others) had joined Bollywood, and the language of songs settled into a pure form of Hindustani (Hindi/Urdu) with minimal English influence. In those decades, lyrics were a central pillar of a song’s appeal, often philosophical, metaphor-laden, and deeply meaningful.

Poetry and philosophy in songwriting: The lyricists of the Golden Age were “no ordinary pen-pushers” but thinkers and poets of high calibre. They infused songs with themes of love, loss, hope, and social commentary in a manner that resonated widely. Songs often carried a philosophical undertone or Sufi-like reflection on life. For example, Sahir Ludhianvi’s famous line “Main zindagi ka saath nibhata chala gaya, har fikr ko dhuen mein udata chala gaya” (I continued to accompany life, blowing away every worry like smoke) from a 1961 film is remembered for its stoic, life-embracing philosophy.

Another iconic song, “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye” from Pyaasa (1957), penned by Sahir, questioned the value of material success with the haunting refrain “…toh kya hai” (…so what if one even gains the world?). Such lyrics transcended their films and became part of Indian cultural lore.

Notably, many songs of the 1950s–60s read like standalone poems. The use of Urdu imagery and Hindustani idioms gave them an enduring quality. Love songs compared lovers to the moon (“Chaudhvin ka chand”), addressed God and unity across religions (as in “Allah Tero Naam, Ishwar Tero Naam”), or mused on time and destiny (as in Kaifi Azmi’s “Waqt ne kiya kya haseen sitam”). Lyricist Anand Bakshi once pointed out that a simple Hindi line could carry profound meaning, citing the prayer-like verse “O saarey jag ke rakhwaale… balwaano ko de de gyaan,” which in context evoked the devastation of war in a 1961 song. In short, the era’s lyrics combined simplicity with depth.

Importantly, lyrics mattered greatly in this era. They were not just filler around a beat; they were often the soul of the song. An analysis of 1970s Bollywood notes that poets like Sahir, Majrooh, Kaifi Azmi, Yogesh, and Gulzar used their “wordsmithery to great effect,” reminding audiences that cinema was “as much art as it was commerce.” In many films, songs carried the narrative forward or conveyed the characters’ innermost feelings through thoughtful words. This was the age when people memorized entire verses of songs, not just the chorus, because of the emotional and literary weight of the lyrics.

Lyricist Gulzar, who began his career in the 1960s, has observed that film lyrics naturally change with society, but that doesn’t mean they lacked quality back then. He believes many modern songs are still brilliantly written, yet he gave a telling example from his own work. In the 2006 film Omkara, Gulzar wrote what he felt was a beautiful, nuanced song, but “the only song that connected with the audience was Beedi Jalaile.” He noted that despite poetic lyrics being written, the public’s affection gravitated to the catchy, rustic item number. This anecdote actually foreshadows the transition in later decades, but in the ”50s–’70s prime, one could say the average listener still hung on every word of a song.

Themes and examples: Songs from the Golden Age often delved into deeper themes: romance was expressed through sophisticated poetry, and even simple emotions were elevated by elegant diction. For instance, the love song “Kabhi Kabhi Mere Dil Mein” (1976, lyrics by Sahir Ludhianvi) reads like a nostalgic romantic poem about memories and fate. Social themes and existential questions also found voice, consider “Yeh Duniya agar mil bhi jaaye” from Pyaasa, which is a scathing indictment of societal greed, or “Jinhe naaz hai Hind par woh kahan hain” from the same film, critiquing social injustices. Patriotic and philosophical songs like “Ae Mere Watan Ke Logon” (1963, by Kavi Pradeep) or “Zindagi kaisi hai paheli” (1971, by Yogesh) moved listeners to introspection.

The 1950s–70s gave us lyrics that were essentially poetry set to music. They featured refined vocabulary (a mix of Urdu and high Hindi), extensive use of metaphor and allegory, and an emphasis on meaning. The lyricists were often literary figures outside cinema, which lent gravitas to their film work. This era established a gold standard for songwriting that many still nostalgically cherish. However, change was on the horizon as Bollywood headed into the late 1970s and 1980s, when both musical style and lyrics would undergo a transformation.

1980s–1990s: Romantic Ballads, Simpler Language, and the Commercial Turn

By the early 1980s, Bollywood music was experiencing a significant shift. The late ’70s had seen the end of the classical “melody era” and the rise of new trends like disco, and with them came changes in lyricism. The 1980s–1990s period was a transitional era where the poetic complexity of earlier decades gave way, in many cases, to simpler, more direct lyrics aimed at mass appeal.

The tone became more casual and “commercial”, with an emphasis on catchy phrases, romantic clichés, and crowd-friendly choruses. However, this era also produced its share of soulful writing and enduring classics, often in the form of romantic ballads or patriotic songs, even as the general trend moved toward accessibility over artfulness.

You May Also Like to Read

- The OTT Revolution: How Netflix and Amazon Prime Changed Bollywood Storytelling

- Bollywood’s Forgotten Decade: The 2000s Films That Were Ahead of Their Time

The disco and mass-market influence: The 1980s have been called “the disco decade” in Bollywood music. As one analysis describes, “old-world music was giving way to a new, loud sound” in the ’80s, and accordingly, “lyrics were now devoid of all nuance and meaning, crass but popular.” This blunt assessment reflects how many 80s songs, especially in big commercial films, prioritized fun and rhythm over poetry. A composer like Bappi Lahiri became famous for his disco tracks with very straightforward (even frivolous) lyrics, for example, “I am a Disco Dancer” (1982) repeatedly asserts the singer’s identity as a disco dancer in plain English, a far cry from the metaphor-laden songs of two decades earlier.

Hindi film songs also began incorporating more English words and slang in this era, as the urban youth culture changed. It was not unusual to hear a chorus like “You are my chocolate candy” or “Come on baby, let’s dance” in the middle of a Hindi song by the late 80s and 90s.

At the same time, the 80s saw a dichotomy in lyrical quality. While many songs were indeed simplistic “leave your brain at home” fun numbers, a parallel stream of films still upheld refined lyrics. Veteran lyricists like Gulzar and Kaifi Azmi continued to write in the 1980s (e.g., the poignant “Tum itna jo muskura rahe ho” from Arth (1982) by Kaifi Azmi) and a new lyricist, Javed Akhtar, transitioned from scriptwriting to songwriting in the early ’80s, bringing thoughtful poetry into films like Saath Saath and 1942: A Love Story.

An Indian Express retrospective notes that even as garish disco songs ruled the charts, “the poetry in films” was kept alive by the likes of Javed, Kaifi, and Gulzar, who “still kept the flag high.” Many of their songs from the ’80s are timeless and sound “contemporary” even to today’s youth because of their genuine lyrical quality.

Simplification and “relatability”: The 1990s furthered the trend of simplifying language. Bollywood entered an era of blockbuster romantic musicals (epitomized by films of directors like Yash Chopra, Sooraj Barjatya, and Karan Johar). The songs in these films were hugely popular and often very melodic, but their lyrics tended to be uncomplicated and universally appealing rather than dense poetry. Lyricist Sameer Anjaan, who emerged in the 80s and became the most prolific songwriter of the 90s, has spoken about the need to adapt to changing times to stay relevant.

He notes how each decade had its linguistic style: “In the 50s, language used to be folkish. In the 70s, khadi bhasha (pure Hindi) made its place. In the 80s, Urdu and other languages were used… In the late 90s, Hinglish became popular.” Indeed, by the late 1990s, a mix of Hindi and English, “Hinglish”, was common in Bollywood songs. For example, the title of the 1998 film Kuch Kuch Hota Hai is a colloquial Hindi phrase with an English cadence, and its songs feature lines like “You know you are my Soniya” (combining English and Hindi).

In fact, Karan Johar originally approached Javed Akhtar to write the lyrics for Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, but Javed refused, finding the very title phrase “kuch kuch hota hai” too frivolous or “vulgar” for his taste. Johar instead hired Sameer, who delivered simpler, more “relatable” lyrics to fit the film’s youthful vibe. This anecdote highlights how the industry’s priorities had shifted; filmmakers wanted lyrics that were easily understood and instantly catchy, even if that meant moving away from the ornate poetry of earlier years.

In the 90s, romantic ballads with straightforward emotions reigned supreme. Songs like “Tujhe Dekha Toh Yeh Jaana Sanam” (from Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, 1995) or “Pehla Nasha” (Jo Jeeta Wohi Sikandar, 1992) expressed love in relatively simple words, yet effectively. Lyricist Anand Bakshi (who wrote Tujhe Dekha… and countless hits in the 90s) was known for using everyday Hindi language that the “common man” could relate to.

According to Amitabh Bhattacharya, a prominent modern lyricist, Anand Bakshi’s lyrics were almost conversational in tone. Bhattacharya, who grew up on 90s music, realized over time “how simple and great those songs really were”, a single Hindi line could convey something big. This indicates that simplicity was not necessarily seen as a bad thing; the best ’90s songs were lauded for clarity and heartfelt emotion.

However, critics of 90s lyrics point out that nuance and poetic flair often took a backseat. The late 90s also saw the advent of the “item number” and splashy dance tracks in commercial films, where lyrics were often nonsensical or purely functional. A song like “Sarkai Lo Khatiya” (1994) became notorious for its cheeky, double-entendre Hindi lyrics; another, “What is mobile number?” (1999) leaned on Hinglish humor. These were a far cry from the genteel wordplay of earlier eras.

Manoj Muntashir, a modern lyricist, observes that there is a “general perception that the quality of language has deteriorated” over time, though he personally feels those grand, flowery old words had their time and today’s simpler style is just different. He quips that Hindi film lyrics have “shed off extra pounds”, implying they’ve lost some ornamentation, but argues that change in language is natural and “times have changed and so has the language.”

Romantic and patriotic resurgence: It’s worth noting that the ’90s weren’t all fluff. In fact, the late 90s brought a wave of patriotic and socially conscious songs alongside the love ditties. The 1997 film Border gave us “Sandese Aate Hain”, a heartfelt song about soldiers longing for home, written by Javed Akhtar. Its lyrics are plain Hindi, yet extremely poignant and poetic in effect, proof that simple words can move a nation.

The 90s also saw A.R. Rahman’s music rise, often accompanied by powerful lyrics (like “Maa Tujhe Salaam” or the Hindi version of “Vande Mataram” in 1997). Meanwhile, poets like Gulzar continued to pen gems, e.g., “Chaiyya Chaiyya” (1998), which brimmed with Sufi imagery and bilingual wordplay, becoming a pan-Indian hit despite (or because of) its Urdu-Punjabi vocabulary. Thus, even as commercialization nudged lyrics toward ease and catchiness, quality writing persisted in many popular songs.

By the end of the 1990s, the inclusion of Punjabi lyrics and Punjabi folk flavor had also become a trend (partly due to many Punjabi-background music directors and the popularity of Punjabi pop). Lyricist Sameer noted (with some concern) that by the 2000s, “songs have become so Punjabi-laden that Hindi is struggling to retain its identity.” This mixing of languages would only intensify in the next decades. Sameer’s comment underscores a feeling that the pure Hindi lyric had become rare; instead, Bollywood songs freely jumbled Hindi, Punjabi, and English.

The 1980s–90s era, then, can be seen as the time when Bollywood’s lyrical style democratized, becoming more inclusive of different languages and more oriented toward immediate audience connection. The lofty Urdu poesy of the 50s had gradually transformed into the colloquial Hindi (and Hinglish) of the 90s.

The 80s and 90s brought a transition from poetry to populism in Bollywood songwriting. There was a noticeable simplification of vocabulary and metaphors, a greater use of catchphrases and repeated hooks (like the counting lyrics of “Ek Do Teen” or the titular “Kuch Kuch Hota Hai” refrain), and an embracing of mass appeal over literary merit.

Yet, the era also proved that simple didn’t have to mean shallow; many 90s songs remain beloved classics because of their genuine emotion and memorable, if plain-spoken, lyrics. The stage was set for the 21st century, where both these trajectories, the quest for instant appeal and the effort to retain meaning, would play out in new ways under the influence of digital media.

2000s–Present: Mass Appeal, Item Songs, and the Rise of Viral Hook Lines

In the 2000s and 2010s, Bollywood lyricism entered a new phase, one that reflects the rapid changes in India’s pop culture and technology landscape. Songs in this era often aim for mass appeal across a diverse, global Indian audience. The craft of songwriting has increasingly centered on creating that one addictive hook, a short, instantly catchy phrase or chorus that can grab listeners.

This period saw an explosion of “item songs” (musical numbers often inserted purely for their crowd-pulling energy), a heavy infusion of Punjabi and English slang into lyrics, and the emergence of viral music trends driven by platforms like YouTube, TikTok, and Instagram. The tone and vocabulary of Bollywood lyrics today are markedly different from the poetic classics of yesteryear, though debates continue on whether this represents a decline in quality or just an evolution in style.

Hook-line culture and item numbers: A defining feature of 21st-century Bollywood songs is the emphasis on hook lines, the memorable catchphrases that get repeated multiple times. Think of songs like “Munni Badnaam Hui” (2010) with its cheeky hook “Munni badnaam hui, darling tere liye” or “Sheila Ki Jawani” (2010) with “I know you want it but you’re never gonna get it”. These songs revolve around a fun, even absurd, central line that listeners can’t get out of their heads.

Lyricist Amitabh Bhattacharya, who himself wrote the mischievously catchy “Emotional Atyachar” (2009), has explained that using everyday colloquial language and phrases people use in daily life helps create a connection. He gives the example of his lyric “chai mein dooba biscuit” (a biscuit dipped in tea), which he put into a dance song simply because it’s a relatable image for every Indian, from Kashmir to Kanyakumari.

This illustrates how modern lyricists often prioritize relatability and phonetic appeal (how fun a phrase is to say or sing) over deep poetry. Bhattacharya openly says, “I am not a poet. My source material is everyday, conversational bol-chaal ki bhaasha.” This is a stark contrast to earlier writers like Sahir or Shailendra, but it reflects the prevailing trend: lyrics that feel like casual chat with the audience tend to click today.

The 2000s also cemented the trend of item songs, high-energy numbers usually geared towards dance and often with suggestive or playful lyrics. These songs frequently feature a repetitive hook line that becomes the song’s identity. Titles often are the hook itself (e.g., “Kajra Re”, “Chikni Chameli”, “Fevicol Se”). The content of item song lyrics is usually simple and rhythmic, sometimes bordering on nonsensical, designed to be instantly infectious. Noted lyricist Manoj Muntashir observes wryly, “Nowadays, writing lyrics has turned more into a quick fix than a serious art.”

He specifically calls out that “rap songs have… added to the amateurish and paralytic writing” in some cases. By “quick fix”, he means that many modern songs are written rapidly to capitalize on trends, with less emphasis on carefully crafted poetry. The rise of rap and hip-hop in Bollywood (especially post-2010) indeed brought a new lyrical style, often blunt, rhythmic, and loaded with English words or slang. This has been a double-edged sword: on one hand, it’s a form of expression that resonates with younger audiences; on the other, purists like Muntashir feel it sometimes sacrifices literary merit and linguistic richness.

Multi-lingual and global influences: Contemporary Bollywood lyrics freely intermingle Hindi with other languages. Punjabi, in particular, has become extremely prevalent. It’s common for a Hindi film song now to have Punjabi choruses or rap verses, as well as English phrases. Irshad Kamil explains that this fusion is the “demand of the current times.” He points out that many urban youth today hardly speak pure Hindi and are more comfortable with either English or regional languages, so film songs mirror that reality.

Punjabi beats and words add energy and pan-Indian appeal, for instance, a song like “Kala Chashma” (2016) mixes Punjabi lyrics with Hindi to create a nationwide dance hit. Sameer Anjaan remarks that the language used in films today is hard to even label because “songs have become so Punjabi-laden that Hindi is struggling to retain its identity.” This might be an exaggeration, but it underscores how thoroughly Bollywood has embraced linguistic masala. There’s also more English than ever before.

A quantitative study of Bollywood lyrics (1995–2015) found a significant increase in the use of English words over the years. Tellingly, it noted that while the most common Hindi word in songs was still “hai” (is), one of the most frequent foreign words was “baby”, a term that hardly appeared in the old classics but is ubiquitous in modern romantic pop songs.

The vocabulary of lyrics has shifted to include contemporary slang, brand names, and pop culture references. For example, songs have casually referenced Facebook, WhatsApp, and selfies (e.g., a 2015 song literally titled “Selfie Le Le Re”). This reflects how lyricists now write with an eye on immediate cultural relevance, even if it means the lyrics may not age as gracefully. Lyricist Raj Shekhar noted that sometimes he is told not to use certain difficult Urdu words in songs on the assumption that today’s listeners won’t understand them.

There is a pressure to “make it more accessible” linguistically. Shekhar, however, feels that Gen Z listeners are quite smart and will understand heartfelt lyrics even if a few elaborate words are used, and indeed, his own hits like “Ishq Hai” (2023) used some Urdu words yet became popular with young audiences. This suggests that while the general trend is towards simplicity, there is still room for creative language if done sincerely.

Impact of streaming and shorter attention spans: Another factor shaping modern Bollywood lyrics is the way music is consumed today. With the advent of music streaming and on-demand listening, the shelf life of songs has changed. Songs are released as singles, promoted on YouTube and social media, and listeners can skip tracks in seconds if not hooked. Lyricist Sameer, with 40+ years in the industry, laments that nowadays people want a song “ready-made” and often pay more attention to the beat than the words, leading to a drop in “lyrical value.”

In his colorful analogy, “modern music is like junk food – it is everywhere”, providing quick gratification but perhaps not much nutrition. He observes that the new generation’s mindset has brought fresh sounds but also “deteriorating” lyrical content, with the sound taking precedence. This is a sharp critique, but one echoed by many veterans.

Musically, songs have also gotten shorter on average, often around 3 minutes, aligning with global trends in pop music aimed at maximizing streaming (where completion rates matter). Shorter songs mean less room for long lyrical verses; instead, a snappy chorus might dominate. Repetition has become a common device, repeating the hook line many times to ingrain it in the listener’s mind (sometimes at the cost of having fewer unique lyrics overall).

Javed Akhtar has commented on the challenge of writing poetry for today’s films: the narratives themselves have changed. “An artist can only go as far as the given art,” he explains, meaning if films don’t have situations that require poetic expression, the lyricist is constrained. He gives the example that in the old days, you might have a poet character in a film (like the hero of Pyaasa) or a literary setting that justified flowery lyrics, but “in today’s cinema, where are the characters like the poet in Pyaasa for me to write poetry?!”.

Modern films often depict contemporary, urban stories with realistic characters; it would indeed feel odd for a present-day college student character to break into an elaborate Urdu nazm. Javed acknowledges this frustrates him, he even refuses some songs if he feels the situation is “too crude” or lacking poetic possibility. This highlights a broader point: Bollywood songs are now tightly woven into a film’s fast-paced narrative or marketing strategy, leaving less room for the kind of abstract, standalone poetry that earlier eras indulged in.

The Social Media Effect: TikTok, Reels, and Viral Lyrics

No discussion of today’s Bollywood lyrics is complete without examining the impact of social media and meme culture. In the last decade, platforms like TikTok (which was hugely popular in India before its 2020 ban), Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have transformed how songs gain popularity. A song’s success today can be propelled as much by a 15-second viral dance challenge as by traditional film promotion. This has led to what some call the “TikTok-ification” of music, where artists and producers deliberately create songs (or at least parts of songs) that will trend in short video clips. The result: an intense focus on that one earworm hook, line, or drop that can become a meme.

Music composer Salim Merchant observes that “these days people are making music that works for Instagram Reels, and it’s really sad.” He notes that some creators put “90% of their effort into a ten-second section of the song” crafted specifically to go viral on Reels, but pay scant attention to the rest of the composition. The assumption is that if a snippet catches on (with a dance move or a meme template), it will drive people to stream the full song, boosting its chart performance.

This strategy has indeed produced viral hits; for instance, the song “Kesariya” (2022) from Brahmāstra garnered massive attention for a particular 15-second segment on social media, even as its overall reception was mixed. A commentator quipped about such cases: “If the hook works, then who cares about the song?”, a tongue-in-cheek summary of the industry’s current hook-first mentality.

The influence of algorithms is so strong that an NDTV op-ed described modern Bollywood as almost subservient to it: “The hook line is the heartbeat; the rest dissolves into oblivion.” Composers today, it says, “engineer earworms designed to vanish as quickly as they arrive,” acknowledging that songs are “shot only as reels – designed not to live in memory, but to chase algorithms.” In other words, the longevity of a song (its emotional shelf life) might be sacrificed for immediate viral fame.

The same piece laments that song picturizations, too, have changed: instead of lavish, story-driven song sequences of the past, now we mostly get music videos with a hook step (a signature dance move) intended for replication on TikTok/Reels. It asks pointedly, “Does anyone remember what comes before or after?” The hook these days implies that audiences often only know the 30-second viral part of the song and not the full lyrics.

From the industry side, record labels and filmmakers are very aware of these trends. A report in Mint noted that labels now often ask artists to ensure there’s a “15-second” high-impact segment in a song, “preferably with a hook step,” that can catch fire on Reels. Singers and composers are consciously structuring songs to include a catchy beat drop or chorus within the first minute, to cater to short attention spans.

Singer Asees Kaur admitted, “I find myself thinking something needs to happen every 15 seconds so listeners don’t leave. Our attention spans have reduced significantly; it’s a scary place to be in as a musician.” This highlights how the craft of songwriting is being influenced by the presumed impatience of the audience, a far cry from the 5-6 minute slow burns of classic songs, which listeners once had the patience to absorb.

Interestingly, social media has also given old songs a new lease of life. As singer Avanti Nagral notes, many older Bollywood songs (from the 80s, 90s, even 60s) have gone viral on Reels purely because they’re good songs, without having been designed for the platform. For example, in 2022, a 90s track like “Srivalli” (actually 2021, but retro style) or even classics like “Chaand Baliyan” (an independent song) became trending audio on Instagram.

And who can forget how “Kala Chashma”, a 2016 song, blew up worldwide in 2022 thanks to a dance clip trend? This shows that while some are chasing viral algorithms, truly well-composed and well-written songs (even from the past) can organically catch the public’s fancy in the meme era. There’s a fine line between writing with a platform in mind and writing a song that stands on its own merit but happens to go viral.

Lyricist Raj Shekhar provides a balanced take: “In the age of reels, you are expected to convey your thoughts in a short time. People also say that a song should have a hook, but I don’t always follow it. While writing a song, I don’t think about making it viral on reels.” Shekhar believes authenticity can still shine through; his viral hit “Ishq Hai” gained popularity on Reels not because he tailored it for that, but because its genuine emotion resonated, hook or not. He also contests the notion that young audiences won’t appreciate meaningful lyrics: if the emotion is honest and the tune is good, even Gen Z will listen (his own success with soulful tracks attests to this).

Social media has unquestionably changed the game. It has popularized the “viral hook line” approach to songwriting and marketing, but it has also created a space where both new and old songs can find success based purely on public whim. The algorithm rewards brevity and catchiness, but audiences still reward quality when they hear it. The best outcomes in recent times have often been when a song manages to tick both boxes, for instance, the rap anthem “Apna Time Aayega” (2019) from Gully Boy became a youth slogan and went viral, yet it also had substantive lyrics about ambition and hard work, penned by a new-age poet (Divine). This dual nature might well define the current era.

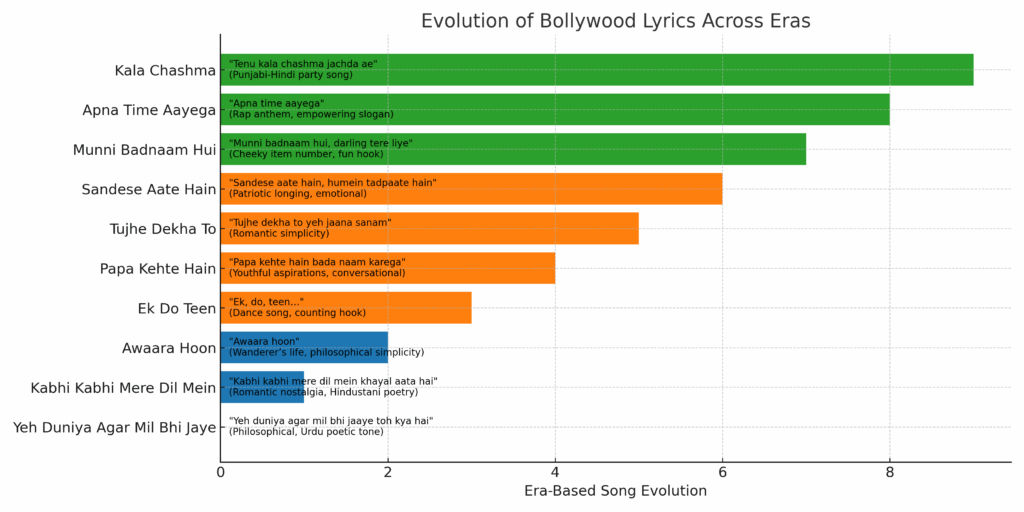

Below is a table highlighting a few iconic Bollywood songs from each era, along with a key lyric line and theme, illustrating how things have changed:

| Era | Iconic Song (Film, Year) | Lyric Highlight | Theme & Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950s–1970s (Golden Age) | “Yeh Duniya Agar Mil Bhi Jaye” (Pyaasa, 1957) | “Yeh duniya agar mil bhi jaaye toh kya hai” (Even if I gain the world, so what?) | Despair at worldly greed; philosophical, Urdu poetic tone. |

| 1950s–1970s | “Kabhi Kabhi Mere Dil Mein” (Kabhi Kabhie, 1976) | “Kabhi kabhi mere dil mein khayal aata hai” (Sometimes a thought arises in my heart) | Romantic nostalgia, elegant Hindustani poetry about love’s memories. |

| 1950s–1970s | “Awaara Hoon” (Awaara, 1951) | “Awaara hoon” (I am a vagabond) | Life of a wanderer; hopeful yet philosophical, simple words with deeper meaning. |

| 1980s–1990s | “Ek Do Teen” (Tezaab, 1988) | “Ek, do, teen…” (One, two, three…) | Dance/party song; ultra-simple counting hook, made for mass appeal and catchiness. |

| 1980s–1990s | “Papa Kehte Hain” (Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak, 1988) | “Papa kehte hain bada naam karega” (Dad says I’ll make him proud) | Youthful aspirations; light, conversational tone that struck a chord with the young generation. |

| 1980s–1990s | “Tujhe Dekha To” (Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge, 1995) | “Tujhe dekha to yeh jaana sanam” (When I saw you, my love, I realized…) | Pure romance; simple heartfelt expression of love, emblematic of 90s romantic simplicity. |

| 1980s–1990s | “Sandese Aate Hain” (Border, 1997) | “Sandese aate hain, humein tadpaate hain” (Letters come and torment us) | Patriotic longing; straightforward Hindi conveying soldiers’ emotions, very poignant and enduring. |

| 2000s–Present | “Munni Badnaam Hui” (Dabangg, 2010) | “Munni badnaam hui, darling tere liye” (Munni became notorious, darling, for you) | Item number: cheeky and tongue-in-cheek, built around a fun hook line that became a national catchphrase. |

| 2000s–Present | “Apna Time Aayega” (Gully Boy, 2019) | “Apna time aayega” (Our time will come) | Rap anthem, empowering self-belief slogan that went viral, showcasing the new hip-hop lyrical style. |

| 2000s–Present | “Kala Chashma” (Baar Baar Dekho, 2016) | “Tenu kala chashma jachda ae” (That black sunglasses suit you) | Party song; Punjabi-Hindi mix, with a bhangra vibe and a hook line that sparked global dance trends on social media. |

(Table: Iconic songs from each era with lyric highlights and themes, demonstrating the shift from poetic, verbose lyrics to punchy hook-driven songwriting.)

Changing Audiences, Evolving Art, Loss or Transformation?

Bollywood’s lyrical journey from the 1950s to the 2020s is a reflection of India’s changing society, audience preferences, and media landscape. So, have we lost the “lyrical quality” of the past, or has it merely taken a new form? The answer, it seems, depends on whom you ask, and perhaps lies somewhere in the middle.

Veteran writers often bemoan a decline. Javed Akhtar has openly said that the standards of lyrics have dropped in modern Bollywood, though he attributes a lot of this to the lack of poetic situations in contemporary stories. Gulzar has noted that while great lyrics are still being written, the public’s taste has shifted; the audience today often embraces the simple, instantly gratifying song over the complex one.

Lyricist Sameer compares today’s music to fast food, suggesting it’s consumed quickly without lasting nourishment, and worries that this trend “is not good for the future.” Manoj Muntashir, although a successful modern lyricist himself, admits that many songs now are treated as disposable products, “quick fixes”, rather than works of art, and he particularly criticizes the glut of mediocre rap verses diluting lyric quality.

On the other hand, many in the industry argue that lyrics have adapted rather than deteriorated. They point out that every era has its share of good and bad writing. As Raj Shekhar put it, “I don’t feel that all old songs are good and all new songs are bad.” He acknowledges that earlier there was a more “literary” approach and classical compositions which have lessened, but he implies that it is something to be mindful of going forward, not an irreversible loss.

Lyricist Irshad Kamil and others emphasize that films and songs are a reflection of society. When society’s language and sensibilities evolve, so will lyrics. Today’s listeners live in a digital, fast-paced world; naturally, they connect with songs that speak their language, whether it’s Hinglish, a mix of Punjabi, or a snappy internet catchphrase.

Lyricist Manoj Muntashir actually defends the newer style to a degree, saying Hindi film lyrics have simply “shed some extra pounds” and become leaner and more direct for modern times. He believes Hindi, as a language, is inherently inclusive and will retain its essence despite assimilating new elements. Indeed, we see that in some of the best contemporary lyrics, a song like “Dil Bechara” (2020) has simple words but profound emotion, and even a quirky upbeat track like “London Thumakda” (2014) seamlessly blends Punjabi folk with fun, relatable lines, charming audiences.

It’s also worth noting that many current lyricists are consciously striving to balance art and trend. Amitabh Bhattacharya, for example, has written goofy hook-filled hits but also deeply poetic songs (e.g., “Abhi Mujh Mein Kahin”, 2012), showing that there is room for quality within the commercial framework. Similarly, writers like Kausar Munir, Varun Grover, and others have delivered lyrics praised for genuine literary merit in recent films, proving that the craft is not dead.

They often hide layers of meaning in plain vernacular language, much like how earlier generations hid social messages in poetic metaphor. In a way, the mission of lyricists remains the same: to amaze or amuse the audience (as Gulzar has said, a song lyric must do either to be remembered), but the method to achieve that has changed.

Audiences, too, have changed. The modern Bollywood audience is fragmented, from village listeners who still enjoy folk-style lyrics to metro youth who jam to rap and EDM. Writing for such a broad audience necessitates a different approach than writing for a homogeneous 1950s crowd hearing songs on Radio Ceylon. One unifying factor today is social media: a song that becomes a meme or a challenge can be shared by all, cutting across demographics.

Thus, we often see songs with very simple, repetitive lyrics become pan-India phenomena (like the recent viral hit “Naacho Naacho” from RRR, 2022). These songs might not win poetry awards, but they fulfill music’s basic purpose of bringing joy and togetherness, whether through dance or sing-along value.

So, has lyrical “quality” been lost? If one defines quality purely by the standards of the Golden Age, intricate Urdu poetry, and complex metaphors, then yes, such songs are rarer now in mainstream cinema. But if we broaden the definition of quality to include effectiveness and authenticity, many modern songs still qualify, albeit in a different way. A 2020s love song using everyday Hinglish can be as honest and heartfelt to today’s generation as a 1960s love song in shuddh Hindi was to that era’s audience. The vehicle of expression has evolved.

Bollywood lyrics have not so much died as evolved. The art form is responding to new stimuli: contemporary culture, new music genres, and new platforms of delivery. Some richness has been inevitably lost in this churn, the vocabulary is less flowery, the poetry less overt. But there’s also a case to be made that today’s lyricists face challenges of brevity and attention that their predecessors didn’t, and many are rising to the occasion by finding creative ways to say a lot with a little.

As long as there are storytellers in cinema, there will be a demand for words that elevate those stories, whether via a soul-stirring ghazal or a whistle-inducing rap verse. The form may continue to change in unforeseeable ways (who knows what the next TikTok-like disruption will be?), But the soul of Bollywood songwriting, conveying emotions through music, remains in play.

Ultimately, audiences will decide what they connect to. Right now, they sway to hook lines and viral beats, but they also tear up to a well-written emotional song. Perhaps the best outcome is an acceptance that evolution is not extinction. The poetic classics aren’t coming back en masse, but their legacy survives in inspiring today’s writers to find a new voice for a new age. As one generation rues the present and another can’t recall the past, Bollywood lyrics move on, sometimes lost in “loots” and “latkes” (dance hooks), and sometimes, quietly, finding their way back to poetry when we least expect it.

The song, in any case, goes on, and as listeners, we are fortunate to have a rich heritage to cherish and a dynamic present to enjoy. Whether humming a complicated Urdu verse or a viral one-liner, India’s love affair with its film songs continues, evolving with each era’s heartbeat.