The period from 2020 to 2025 has transformed the economics of Bollywood films. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–2021 brought an unprecedented disruption – theaters were shut for months, big releases were postponed, and many cinemas suffered heavy losses. With audiences stuck at home, OTT platforms (like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Disney+ Hotstar, etc.) became a lifeline for the film industry. Producers who once focused purely on theatrical box office had to embrace digital streaming to reach audiences. As theaters gradually reopened in 2022, the industry saw that viewer habits had shifted. Movies that might have easily crossed ₹100 crore in pre-pandemic times were now struggling to hit even ₹50 crore in theaters. This lower box office benchmark doesn’t always mean a film is a failure, it reflects that many viewers are now watching from home. Indeed, films can remain financially profitable despite modest theater collections by leveraging multiple revenue streams like streaming and satellite TV rights.

In this changing landscape, Bollywood had both surprising hits and high-profile flops that taught the industry important lessons. For example, in 2022 the modest-budget The Kashmir Files became a blockbuster with over ₹250 crore domestic collections, despite no big stars, because of strong content and word-of-mouth. In contrast, Aamir Khan’s star-studded Laal Singh Chaddha (2022) barely managed ₹60–70 crore in India, a flop relative to its big budget. The contrast showed that content, budget control, and timing have become more crucial than ever for box office success. Production houses and filmmakers have started to adjust their strategies, focusing on cost-effective projects, exploring digital premieres, and creating franchise films, to align with the new economic reality of Bollywood.

Contents

- Film Budgets and Revenue Streams Simplified

- Theatrical Earnings and Profit-Sharing Explained

- The Rise of OTT Streaming Revenue

- Pre-Release Deals: Satellite, Music, and Other Monetization

- Case Studies: Hits, Flops, and Financial Lessons

- How Production Houses Adapt Strategies for Profit

- Looking Ahead: The Road to Sustainable Cinema Economics

Film Budgets and Revenue Streams Simplified

Every Bollywood film begins with a budget, which is the cost of making the movie (including actor fees, sets, special effects, marketing, etc.). Big star action films might have budgets well above ₹150–200 crore, while smaller content-driven films can be made in ₹20 crore or less. Recovering this cost and earning profit is the ultimate goal. Unlike a decade ago when theater ticket sales were the primary income, today a film’s revenue comes from multiple streams. The major revenue streams for a typical Bollywood film include:

- Theatrical Box Office: This is the money earned from cinema ticket sales. It remains the largest share of a film’s revenue, roughly 65–70% of total earnings on average. The domestic box office (India) usually contributes the bulk (about 80–85% of the total box office) while overseas markets (North America, UK, Middle East, etc.) add the remaining 15–20%. For instance, a blockbuster like Pathaan (2023) grossed around ₹654 crore in India and about ₹396 crore overseas, totaling over ₹1,050 crore worldwide, showing how overseas collections can significantly boost overall earnings.

- Digital/OTT Rights: Selling the streaming rights to an OTT platform is now the second-biggest revenue source, contributing roughly 15–20% of a film’s earnings. Platforms like Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hotstar pay hefty sums to acquire films. Sometimes these deals are done before a film’s release, providing upfront cash to the producer. The pandemic greatly accelerated this trend, for example, in 2020, many films skipped theaters and premiered online. In such cases, the lump sum from OTT effectively replaced box office revenue. Even for theatrical releases now, the post-theatrical streaming rights are often sold in advance as a crucial part of the film’s revenue model.

- Satellite TV Rights: Indian films often sell rights to broadcast on television (satellite channels). This used to be the second-largest revenue stream, but with the OTT boom it now forms about 5–7% of revenue. Still, satellite rights can be lucrative, especially for mass entertainers that draw family audiences on TV. Many big movies strike deals with channels like Zee Cinema, Sony, or Star TV for exclusive telecast after the theatrical run. This provides additional income – sometimes a popular film can earn tens of crores from a TV rights deal.

- Music Rights: Bollywood films are known for their songs, and music rights (audio and video) contribute around 3–4% of total revenue. Music companies (like T-Series, Sony Music) pay the producer for the soundtrack. In return, they monetize through streaming platforms, radio, and YouTube. For hit music albums, this can be a sizeable amount. For example, a movie with popular songs might recover a chunk of its budget by selling the album rights and garnering millions of streams/views that generate advertising revenue.

- Ancillary Streams: Other sources make up the remaining small share (roughly 2–3%). These include brand tie-ups, merchandise, in-film product placements, remake rights, and home media sales. While each ancillary stream isn’t huge alone, together they add a bit of “icing on the cake” for the film’s finances. For instance, a movie might tie up with a soft drink brand for promotions, or later sell remake rights to another language if the story has wide appeal.

By piecing together income from all these channels, producers try to ensure a film is profitable. It’s not unusual now for a film to cover most of its cost before release by pre-selling various rights. If a film’s production budget is ₹100 crore, the maker might aim to secure perhaps ₹50–60 crore from digital, ₹10–15 crore from satellite, ₹5 crore from music, and some from distribution presales, so that theatrical box office needs to cover only the remaining amount to break even. In fact, some smaller films in recent years made profits even before theatrical release, for example, Indoo Ki Jawani (2020) recovered its cost through digital and satellite deals before it even hit cinemas. This kind of pre-release revenue buffering has become a common risk-reduction strategy in Bollywood.

Theatrical Earnings and Profit-Sharing Explained

When a film releases in cinemas and tickets are sold, how is this theatrical revenue distributed? Understanding this is key to box office economics. The money from ticket sales (gross box office) first has taxes removed (government GST on cinema tickets). The remaining amount is called the net box office. This net collection is then split between the exhibitors (the theater owners) and the distributors (who released the film in that territory). The distributor in many cases has already paid the producer for the rights, so effectively the distributor’s share of ticket sales is what recoups their investment and brings profit to either the distributor or, indirectly, the producer.

In India, the exhibitor-distributor split often works on a sliding scale over the weeks of release. In multiplex theaters (the large cinema chains), a distributor typically gets about 50% of the net box office collections on average. In practice, the deal might be 52% to the distributor in the first week (meaning the cinema keeps 48%), then the distributor’s share might drop to around 42% in the second week, and further to 30% by week four. This decreasing share is designed to encourage multiplexes to keep movies running longer, by week four, the theater keeps a larger cut (up to 70%) as an incentive to continue screening a film that still draws crowds.

You May Also Like to Read

On the other hand, single-screen theaters (the standalone cinemas) often operate on different terms. They tend to offer a higher percentage (sometimes 70–90% of ticket sales) to distributors from the very first week, because single screens rely on big movies provided by distributors and have to offer more generous terms to get those films. In summary, roughly half of the box office money goes back to the film’s distributor, and the other half stays with theater owners for running the cinemas.

Now, how do producers fit into this? It depends on the distribution model used for the film:

- In many cases, producers sell distribution rights for different regions to distributors before release. A distributor in, say, Delhi territory, might pay a fixed amount (a Minimum Guarantee) to the producer for that region’s rights. Under the Minimum Guarantee model, the distributor keeps all their share of tickets and does not owe the producer anything more; importantly, if the movie underperforms, the loss is the distributor’s, the producer does not refund the money. This model shifts risk to the distributor and is very common, as producers prefer to secure their money upfront.

- Other models include an Advance with Refund: the distributor pays an advance to the producer but if the box office is below a certain threshold, the producer agrees to refund some money (sharing the loss). This is less common, but sometimes done to convince distributors to take a big film with uncertainty. There is also a Commission model, where the distributor does not buy the film outright but releases it on behalf of the producer for a fee or percentage. In that case, after theaters have taken their cut, the remaining distributor share goes to the producer, and the distributor only takes a commission cut for their services.

Each model balances risk differently between the producer and the distributor. In Bollywood, outright sale (Minimum Guarantee) is preferred by producers since it ensures producers recover costs early and are safe from flop losses. Distributors accept this risk hoping the film is a hit so that their share of tickets exceeds what they paid (giving them profit). However, when distributors pay a hefty price and the film flops, they can lose big money. In 2022, after a series of big-budget flops like Laal Singh Chaddha and 83, many distributors lost money. There were instances where producers had to compensate distributors to maintain goodwill.

This is not a legal requirement if the deal was MG, but a gesture to keep relationships healthy, if distributors bleed, they may be wary to buy the producer’s next film. For example, after Laal Singh Chaddha underperformed, the producers reportedly refunded a portion of the losses to major distributors as a goodwill gesture. This scenario reinforced that mis-pricing a film (selling rights at an exorbitant rate assuming it will be a blockbuster) can lead to a lose-lose outcome.

Another layer is the producer-exhibitor relationship. Sometimes big producers (or studios) release the film themselves (without selling to a middle distributor) especially in key territories. In such cases, the producer directly takes the distributor’s share from theaters. This can yield more profit if the film succeeds (no middleman), but also exposes the producer to full risk if it fails. Many top studios (like Yash Raj Films or Disney UTV) distribute their own big films nationwide, essentially acting as their own distributor. For instance, YRF distributed Pathaan itself; since the film was a blockbuster, YRF as producer-distributor enjoyed the full 50% of net box office share, which was huge. But if the film had flopped, they would have borne that loss entirely. Thus, producers decide on distribution strategy based on their risk appetite and confidence in the film.

The Rise of OTT Streaming Revenue

Bollywood embraced direct-to-digital releases during the pandemic. A collage of 2020–21 films like Gulabo Sitabo, Laxmii, Coolie No.1, and others that premiered on streaming platforms instead of theaters, highlighting the industry’s shift towards OTT platforms.

One of the biggest shifts in Bollywood economics from 2020 onwards is the surging importance of OTT (Over-The-Top) streaming platforms. When theaters shut during the pandemic, streaming services became the new “box office” for many films. Dozens of Hindi films that were initially meant for cinema ended up releasing online directly. Big stars who had never skipped theaters before were suddenly launching their films on Amazon Prime Video, Netflix, Disney+ Hotstar, or ZEE5. For example, Gulabo Sitabo (starring Amitabh Bachchan and Ayushmann Khurrana) was one of the first major films to premiere online in June 2020 instead of theaters. This was followed by movies like Laxmii (Akshay Kumar’s horror-comedy), Coolie No.1 (Varun Dhawan’s comedy remake), Shakuntala Devi, Gunjan Saxena, and many more going straight to digital platforms.

OTT platforms offered lucrative deals to producers at a time when theatrical revenue was uncertain. In a direct-to-OTT sale, the platform pays a fixed price for exclusive streaming rights. This price often depends on the film’s star cast and expected popularity. Trade reports in 2020 indicated that some platforms were willing to pay over ₹70–₹100 crore for anticipated Bollywood movies to release online. For instance, it was reported that Coolie No.1 fetched around ₹80 crore and Laxmii around ₹100 crore from Amazon Prime Video and Disney+ Hotstar respectively. While those films might have earned similar figures in a normal box office scenario, the OTT deal gave producers certainty and immediate recovery without worrying about audience turnout or theater restrictions.

As theaters reopened by late 2021, the craze for direct-to-digital releases slowed down. Producers found that a combined theatrical plus OTT strategy usually yields better total returns than OTT alone. Typically, a film now enjoys a theatrical window first, and then moves to a streaming platform after a few weeks. However, the streaming rights values remain very high. The difference is that now these rights are for post-theatrical release rather than premiere. In 2022–2023, streaming deals continued to contribute a huge chunk to a film’s income. A popular film’s OTT rights can easily be ₹50–₹100 crore or more, depending on competition among platforms. For example, Shah Rukh Khan’s movies are in high demand: a streaming giant like Netflix or Amazon might pay top dollar for the exclusive rights after the cinema run. Recently, there was buzz that Amazon Prime Video paid a record sum for post-theatrical streaming rights of big upcoming titles.

The rise of OTT has also influenced audience behavior and risk for theaters. Many viewers now prefer to wait just a few weeks for a film’s digital release instead of visiting the cinema, especially for non-event movies. Noticing this, some filmmakers have voiced concern. Actor-producer Aamir Khan, for instance, argued in 2025 that the theatrical window (the gap between cinema release and OTT availability) has become too short, possibly hurting box office collections. He pointed out that if people know a film will be “free” on a streaming subscription in 6–8 weeks, they are less inclined to buy a theater ticket. As a result, there are discussions in the industry about extending the theatrical exclusivity period for big films to encourage more cinema footfall. It’s a delicate balance, producers want the OTT money (which comes with an early release on the platform), but they also want robust theatrical income.

Despite these concerns, digital streaming revenue has firmly established itself as a pillar of Bollywood’s business model. OTT platforms not only provide revenue but also a global reach, an Indian film can be seen worldwide on Netflix/Amazon, expanding its audience beyond the diaspora in theaters. Some films that failed in cinemas found a second life on OTT through word-of-mouth. Moreover, direct-to-OTT isn’t off the table for certain projects even in 2023–2025; if a film is niche or mid-sized, producers sometimes choose an OTT premiere to avoid the risk and cost of a theatrical release. The key takeaway is that streaming is no longer an afterthought, it’s now a core part of film economics and often features in a producer’s recovery plan from the outset.

Pre-Release Deals: Satellite, Music, and Other Monetization

Long before a film’s release date, Bollywood producers are busy striking deals to monetize their content. These pre-release businesses can significantly determine whether a film is financially safe or not by the time it hits the screens.

Satellite Rights (Television): Selling a new film’s satellite TV rights (for cable and broadcast) has been a standard practice for over two decades. Prior to the OTT era, a film’s sale to a TV network for premiere could fetch enormous amounts, sometimes covering a large chunk of the budget for star-led films. From 2020 to 2025, satellite rights remain valuable, though slightly overshadowed by streaming. Family-oriented entertainers and action blockbusters still command high prices on television because a TV premiere can attract millions of viewers. For example, a Salman Khan movie often gets sold to a major channel for a hefty sum, ensuring the producer makes money regardless of box office.

The satellite deal is usually done pre-release or right after release, locking in that revenue. However, many TV channels now negotiate knowing that the film will also go to OTT, which can reduce exclusive value. As mentioned earlier, on average, around 5% or more of total film revenue comes from satellite deals, but this varies. Some films that flop in theaters still reach a wide TV audience on their premiere night, giving them a second chance to recoup money through ad revenues for the channel (though the producer’s income was the fixed sale price).

Music Rights: Music is integral to Bollywood, and the songs of a movie start generating buzz even before the film’s release. Music companies compete to buy the music rights of big films. In recent years, T-Series (India’s largest music label) has even co-produced films largely to secure music (and sometimes streaming) rights. The music rights sale usually happens during production or post-production. For a film with a popular soundtrack, music rights can bring in a substantial fee, often a few crores of rupees, depending on how much confidence there is in the album’s success. This money is essentially guaranteed income for the producer.

You May Also Like to Read

After buying the rights, the music label earns from album sales (mostly digital now), streaming on apps (like Spotify, Gaana), YouTube video views, and caller tunes. In the 2020s, while physical album sales are negligible, the online streaming of film songs is massive, and Bollywood songs regularly garner hundreds of millions of views on YouTube, generating advertising revenue for the rights holder. From the film’s perspective, music rights might contribute around 3–4% of total revenues, but it can be higher if the music is a big hit. Notably, even films that fail at box office can have superhit music albums (for example, the film Album X might flop, but its love song tops the charts and the music rights still made money).

Other Pre-Release and Ancillary Deals: Producers also look at brand partnerships and product placements before release. It’s common now for a movie to tie up with brands for mutual promotion. For instance, a lead actor might be seen using a particular phone or drinking a soda in the film, and that brand pays sponsorship money. Or the film’s stars appear in TV commercials for a brand as part of the marketing campaign. These deals might not be huge individually, but they could cover part of the marketing expenses. In some cases, a movie franchise might license merchandise (action figures, apparel), though in Bollywood this is not as big as Hollywood merchandising, it’s growing for superhero or kids’ films.

Another important aspect is pre-release distribution rights sales to different territories (which we touched on in the profit-sharing section). For example, a producer might sell the North India rights, South India rights (for the Hindi film’s dubbed versions or just the Hindi screenings in those states), and overseas rights to various distributors or sub-distributors. These sales bring in cash upfront. Collectively, this is often referred to as a film’s “pre-release business”. Trade analysts often report that “Film Y has done ₹XYZ crores pre-release business,” which includes all advances from distributors plus satellite, music, and digital presales. A high pre-release business number is a good sign for producers, as it means most of their investment is already covered. However, it could be a warning sign for distributors if that number is based on very optimistic assumptions. For instance, if a film’s rights are sold very high price and the film underperforms, distributors stand to lose money (as happened with some 2022 flops).

Post-Theatrical Monetization: Even after a film completes its theatrical run and initial release cycle, it can continue to make money. The most common post-theatrical revenue comes from longer-term licensing. After a film’s first cycle on OTT or satellite, it can be resold or renewed. For example, after a few years, TV channels might acquire older hit films at lower rates to fill their movie slots, a classic film like Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge still gets TV reruns decades later under licensing deals. Likewise, streaming platforms rotate content: a film might be on Netflix for a year, then move to another platform or come back after some time, each time earning some licensing fee for the rights holder. Airlines and hotels also license movies for in-flight or on-demand entertainment. These amounts are not huge for one film, but they add up over time, especially for the library content of big studios.

Finally, a unique monetization route is when Bollywood content finds overseas special markets. For example, some Indian films get released in non-traditional markets (like Turkey, Japan, or China) much after their Indian release, which can bring additional box office or streaming revenue. A film like Dangal (2016) famously made a huge gross in China a year after its Indian release, though this kind of success is rare and not seen in 2020–2025 due to political and market factors. Nonetheless, producers remain on the lookout for any avenue to maximize a film’s lifetime value.

The financial fate of a film is determined by a combination of all these streams. The theatrical box office is just one piece of the puzzle now. A film that underwhelms in theaters might still break even or profit thanks to pre-sales and post-theatrical revenue. Conversely, a film that skews too expensive might still be in trouble even if it grosses decently, if it didn’t secure enough ancillary income. The smart play for production houses is to balance these sources, not relying solely on one big hit source, but piecing together many sources to build a profitable venture.

Case Studies: Hits, Flops, and Financial Lessons

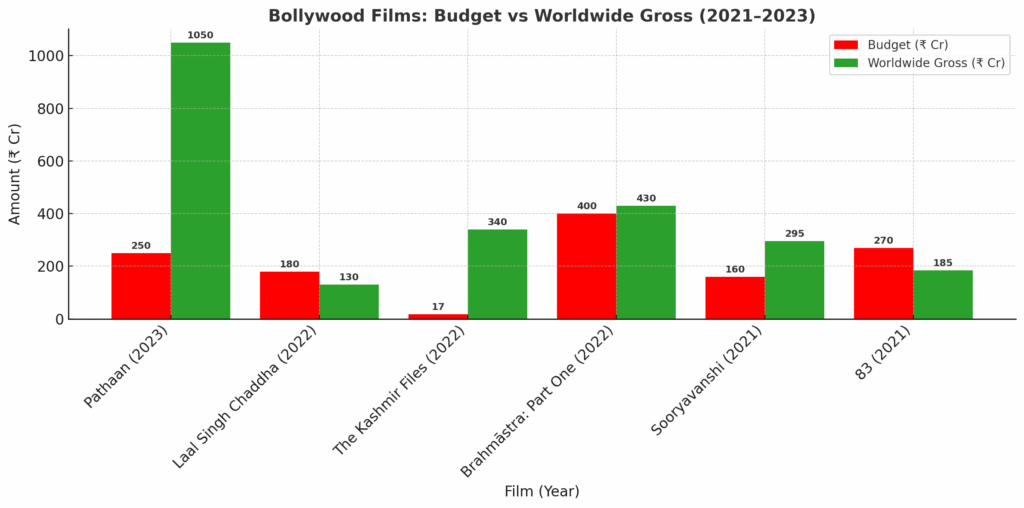

To better understand Bollywood’s box office economics, let’s look at a few real examples from recent years (2020–2023) and see how their budgets and collections translated into success or failure. The table below compares a mix of major hits and flops, illustrating the financial dynamics:

| Film (Year) | Approx. Budget | Domestic Gross | Overseas Gross | Worldwide Gross | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathaan (2023) | ₹250 crore | ₹545 crore (net in India) ≈₹654 crore gross | ₹396 crore | ~₹1,050 crore | Blockbuster – huge profits globally. |

| Laal Singh Chaddha (2022) | ₹180 crore | ₹70 crore net (India) ≈₹85 crore gross | ₹60 crore | ~₹130 crore | Flop – big loss; only ~₹130 cr return on a high budget. |

| The Kashmir Files (2022) | ₹15–20 crore | ₹253 crore net ≈₹298 crore gross | ₹43 crore | ~₹340 crore | Blockbuster – extraordinary ROI due to low budget. |

| Brahmāstra: Part One (2022) | ₹400 crore | ₹257 crore net (all languages) ≈₹315 crore gross | ₹115 crore (est.) | ~₹430 crore | Semi-Hit / In-between – huge gross but extremely high budget makes profit margin thin. |

| Sooryavanshi (2021) | ₹160 crore | ₹233 crore gross (India) | ₹61 crore | ~₹295 crore | Hit – recovered costs in a post-pandemic market. |

| 83 (2021) | ₹270 crore | ₹102 crore net (India) (approx) | ₹58 crore (approx) | ~₹180–190 crore | Flop – high-budget sports drama that failed to recoup costs. |

Table: Examples of Bollywood film economics (2020–2023). Budget figures are approximate. A film’s success depends on the relationship between cost and total collections. “Domestic” refers to Indian box office, and “Overseas” refers to the international box office. Worldwide gross is the total of both.

Looking at the table, some insights emerge:

- High Budget + Mediocre Collection = Trouble: Laal Singh Chaddha and 83 demonstrate that even with notable stars, overspending can be dangerous. Laal Singh Chaddha earned around ₹130 cr worldwide on a ₹180 cr budget, even after adding whatever came from OTT or satellite later, it likely didn’t break even. Such films left distributors in losses, prompting refunds and rethinking of green-lighting very expensive projects without assurance of audience interest (especially in a changing audience taste landscape).

- Low/Mid Budget + Strong Collection = Big Profits: The Kashmir Files is a standout example. Made for under ₹20 cr, its ₹340 cr worldwide gross made it one of the most profitable Hindi films ever in terms of percentage return. Another example not in the table is Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2 (2022), a mid-budget horror-comedy that became a clean hit by earning about ₹250 crore globally on a modest cost. These cases teach that controlled budgets combined with content that clicks with the audience can yield better ROI than star vehicles. Production houses have taken note, showing more interest in modest projects with good scripts.

- Blockbusters Still Matter for Big Money: Pathaan shows that event films can still draw huge crowds and revenues. Its blockbuster success (over ₹1000 cr gross) not only recovered its hefty budget but also made hefty profits for Yash Raj Films. Such successes help studios compensate for other flops in their slate. However, not every big-budget film is a Pathaan. The mixed outcome of Brahmāstra (great revenue but borderline profits due to enormous costs) indicates that scale alone isn’t enough; the spend must be justified by earnings. Bollywood studios are now more cautious: they will spend big only on films that promise franchise potential or pan-India appeal, and even then, they often partner with other studios to spread the risk.

- Overseas and Ancillary Earnings Can Tip the Scales: In some cases, overseas box office has rescued a film’s economics. For example, a movie like Dilwale (2015) was average in India but did well abroad, helping it recover costs. In our period, Laal Singh Chaddha at least got a somewhat decent overseas reception (around ₹60 cr overseas), which softened the blow a little. Moreover, OTT rights sales after release can recoup part of the losses. 83, though a theatrical flop, was later released on Netflix and Star Gold (satellite), which would have given some return. These additional earnings might determine if a film ends up losing money or eventually breaking even. Thus, a film’s fate isn’t sealed on theater collections alone; the full picture emerges after considering all revenue avenues.

Each film’s performance teaches stakeholders about risk management. Bollywood producers have started to use more data and analytics to predict revenues (e.g., Ormax Media’s box office tracking, social media buzz metrics) and set budgets accordingly. If a particular genre or star’s films are seeing diminishing returns, producers either negotiate lower star fees or scale down production costs for those projects (this happened after 2022 when several superstar-led films flopped; reports suggested actors like Akshay Kumar, whose 2022 films underperformed, had to reconsider their high upfront fees). On the other hand, seeing the success of certain formulas, e.g., nostalgia and comedy in Bhool Bhulaiyaa 2, or action spectacle in Pathaan, the industry is more inclined to invest in those directions.

How Production Houses Adapt Strategies for Profit

In light of evolving profit models, Bollywood’s major production houses and studios have been adjusting their strategies between 2020 and 2025 to remain financially successful:

1. Balancing Theatrical and Digital: Studios are now planning releases with a hybrid mindset. They design big-screen extravaganzas for theaters (to maximize box office) and simultaneously plan for a quick digital rollout to capture streaming audiences. Some production houses have even launched separate divisions for digital content. For example, Dharma Productions (Karan Johar’s company) created Dharmatic Entertainment to produce web series and films directly for OTT platforms, acknowledging that not all content needs a theatrical release. By diversifying, a studio ensures that even if one channel underperforms, another can compensate.

2. Content is King, Marketing is Queen: There is a greater focus on strong content and scripting at the outset, a lesson reinforced by the success of content-driven hits. Production houses are more frequently collaborating with new writers and directors who can bring fresh stories that work both theatrically and on streaming. Meanwhile, marketing strategies have also evolved. It’s not enough to just splash money on promotions; targeting the right audience segment is crucial. For high-budget films, marketing now emphasizes event-like hype (to draw people to cinemas). For smaller films or OTT releases, the marketing is more digital and word-of-mouth oriented. Essentially, producers want to ensure money is spent in the right place: on improving the product (film) and then efficiently selling it to the audience. If either is weak, financial returns suffer.

You May Also Like to Read

3. Star Salaries and Profit-Sharing: One of Bollywood’s open secrets is that top stars take a huge chunk of a film’s budget as fees. In the mid-2010s, some star fees skyrocketed, which started to pinch when box office returns slowed. Between 2020 and 2022, as big films underwhelmed, producers pushed back on exorbitant star fees. There’s a trend (at least in discussion) towards linking star remuneration with a film’s performance. For instance, a star might take a somewhat lower upfront fee but a share in profits if the movie hits certain milestones. This aligns the star’s interests with the film’s success and reduces the burden of a high fixed cost. Some actors have agreed to such models, especially when reviving projects after a flop, it shows confidence in the content and gives the project a better chance to break even. This shift is gradual, but it indicates a maturation in understanding that a sustainable business model is one where risk and reward are shared.

4. Franchise and Universe Building: Inspired by Hollywood (and successful Indian franchises like Baahubali in Telugu cinema), Bollywood studios are keen on building franchises and cinematic universes. The reason is financial security: a known franchise guarantees a certain audience base and easier marketing. Yash Raj Films, for example, created the “Spy Universe,” linking hits like Ek Tha Tiger, War, and Pathaan. The success of one film in the series boosts interest in the others, and cross-over cameos create hype that translates to ticket sales. Similarly, Rohit Shetty’s cop universe (Singham, Simmba, Sooryavanshi) has become a bankable brand. Production houses are investing in such long-term properties because they allow reusing characters and branding, lowering marketing costs and ensuring a minimum buzz. Even on OTT, they spin off series from movie characters and vice versa. All this expands the revenue streams (imagine theme park attractions or merchandise in the future, if these franchises grow big enough).

5. Cost Control and Smart Production: After the sobering pandemic period, there is more emphasis on cost control. Many studios renegotiated contracts with vendors, got better insurance coverage for shoots (important after COVID delays), and adopted technology to streamline production. For example, virtual sets and CGI are being used smartly to avoid extremely costly on-location shoots, unless necessary. Some producers also stagger their investments; instead of spending ₹200 cr on one film, they might make two films of ₹100 cr each in different genres, hedging bets that at least one will succeed. In other words, diversification of the film portfolio is a strategy: a mix of big-ticket films, medium-budget stories, and direct-to-digital projects. This way, the success of one can cover the shortfall of another.

6. Redefining Success Metrics: Importantly, production houses now look at overall ROI (Return on Investment) rather than just box office glory. A film might be labeled only a “moderate success” at the box office but could be highly profitable due to a low budget and good satellite/digital deals. Conversely, a film touted as a “100-crore grosser” might still lose money if it costs too much. Studios are becoming savvy in analyzing these numbers. The pandemic taught them to value each revenue stream, as highlighted by the fact that even ₹50 crore in theaters can be fine if another ₹50+ crore comes from OTT and TV. The yardstick for success is thus more holistic. This is why in trade discussions post-2022, a ₹50–60 crore theatrical collection is sometimes celebrated if the film’s budget was, say, ₹20 crore and it also earned ₹30 crore from OTT. In earlier years, ₹50 crore would be considered modest, but context matters. This shift has been openly discussed in Bollywood circles, indicating a more pragmatic approach to evaluating a film’s performance.

Looking Ahead: The Road to Sustainable Cinema Economics

Bollywood’s box office economics from 2020 to 2025 have undergone a sea change. The industry learned the hard way through pandemic losses, OTT disruption, and a series of hit-or-miss experiments. Moving forward, a few clear themes are emerging in the quest for a sustainable financial model:

- Flexibility is Key: Production houses must stay flexible in release strategies, theaters for when the film warrants the big screen, OTT for niche or experimental stories, and sometimes hybrid models. The years ahead may see even more fluid windows (perhaps short exclusive runs in cinemas, followed by quick digital release to capitalize on buzz).

- Audience Insight Drives Profit: Understanding what the audience wants to watch (and where they want to watch it) has never been more crucial. Data from OTT viewing habits, social media trends, and feedback are helping studios green-light projects that have a higher chance of striking a chord. Films that align with audience demand tend to do well across platforms, thus making money from every avenue.

- Risk Mitigation: The concept of risk management now sits at the core of film financing. We will likely see producers taking insurance for big-budget films, not just for accidents on set but maybe even for revenue shortfall (in some countries, companies insure a minimum revenue, though it’s tricky). Co-production deals will also be common, sharing cost and profit between multiple studios to spread risk. For instance, if two studios co-produce a ₹200 crore film, each bears ₹100 crore; if it’s a flop, the loss is halved, if it’s a hit, they share the spoils. This was seen with films like Brahmāstra (co-produced by Dharma Productions and Star/Disney) where the burden was shared.

- Emerging Revenue Streams: New monetization methods are on the horizon, from releasing films in multiple languages (Pan-India releases) to tapping into fandom culture (collectibles, special director’s cut releases online, etc.). Bollywood saw how South Indian film industries gained nationwide box office by dubbing their films and creating pan-India appeal (Pushpa, RRR, KGF 2 in 2021–22 drew huge Hindi audiences). Now, more Hindi filmmakers might try to capture not just the Hindi belt but regional markets and overseas diaspora in one go to maximize revenue. Additionally, with digital content booming, successful movie IPs might spin off into web-series (and vice versa), creating an ongoing loop of engagement and revenue.

In conclusion, Bollywood is blending the old and new in its business: the glamour of the box office and the savvy of modern multi-platform commerce. For the common movie fan, this behind-the-scenes economics means we’ll continue to see big theatrical spectacles and enjoy a diverse range of content at home. For the industry, it’s a challenging yet exciting era of reinvention. The films that get made and how they earn money will be shaped by the lessons of 2020–2025, an era that taught Bollywood to be resilient, resourceful, and responsive in the business of cinema.