The 2000s were a transformative period for Bollywood. As Y2K ushered in new technology and globalization, Hindi cinema was navigating its own identity crisis. Amid blockbuster romantic sagas and formulaic action flicks, a parallel stream of films emerged that didn’t quite fit the mold. Many of these movies were misunderstood at release, some crashed at the box office or puzzled critics, yet years later they shine as ahead-of-their-time gems.

Today, thanks to streaming platforms, social media discussions, and anniversary re-releases, audiences are rediscovering these films and acknowledging their visionary themes and styles. This article delves into those Bollywood films from 2000–2009, across both mainstream and independent cinema, that were critically or commercially underappreciated in their day but are now celebrated as cult classics and trendsetters. We will also draw parallels with regional films of that era that influenced or mirrored Bollywood’s trajectory.

Contents

- Mainstream Misfires Turned Cult Classics

- Trailblazers of Indie Cinema in the 2000s

- You May Also Like to Read

- Regional Cinema Mirrors and Influences

- Then vs Now: Reception Comparison

- Legacy and Current Relevance

Mainstream Misfires Turned Cult Classics

Bollywood in the early 2000s was dominated by safe formulas, family dramas, candyfloss romances, and star-driven extravaganzas. It was the age of Karan Johar ensembles and Sooraj Barjatya’s saccharine joint-family films. Yet, a few daring mainstream projects bucked the trend. These films featured big stars or big banners, but their offbeat themes initially baffled audiences. Years later, they have earned cult followings and newfound respect.

Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani (2000): Riding high on the success of 90s romance, Shah Rukh Khan took a risk with this Aziz Mirza satire on sensationalist news media and political corruption. The film, about rival TV reporters and a common man framed by politicians, “didn’t find many takers” in an era when audiences expected feel-good romance. With its dark comedy tone and a climax denouncing media manipulation, it was “written off” as a “complete disaster” at the time.

Two decades on, Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani seems eerily prophetic. In today’s world of 24×7 news and fake scandals, the film’s commentary on TRP-driven journalism feels spot on. What once felt out of place in 2000 is now lauded for being ahead of its time. Even Shah Rukh Khan has reflected on his failure, making him stronger, acknowledging how special the film was despite the initial rejection.

Nayak: The Real Hero (2001): This Anil Kapoor starrer imagined an everyman becoming Chief Minister for a day to clean up the system, a high-concept political fantasy. While S. Shankar’s original Mudhalvan (1999) was a hit in Tamil, the Hindi remake Nayak surprisingly flopped. Audiences in 2001 perhaps weren’t ready for its unapologetic anti-corruption message. As Man’s World notes, “if the film were released today, it would have made a mad collection at the box office.”.

Indeed, the scenario of a common man challenging a corrupt establishment resonates strongly in the post-Anna Hazare era of anti-graft sentiment. Nayak has since become a beloved TV rerun, with its scenes (like the one-day-CM challenge) achieving iconic status. The movie’s premise anticipated the real-world trend of outsider politicians; one can’t help but see reflections of it when former activists or actors take on political roles now.

Dil Chahta Hai (2001): Farhan Akhtar’s directorial debut was not a flop per se; it earned decent reviews, but it “wasn’t a massive hit” in theaters. Many older viewers found its casual, conversational tone and urban yuppie setting unfamiliar. Yet, this tale of three friends redefined the coming-of-age genre in Bollywood. Dil Chahta Hai is now hailed as the millennial friendship film that “every ’90s kid grew up watching… on television”, becoming “a guide to friendships, love, and growing up”.

Its yuppie characters, Goa road trips, and blend of humor and realism were revolutionary for 2001 and set the template for countless Bollywood buddy films that followed. The film’s cult status grew gradually through cable re-runs and DVDs, an example of a trendsetter recognized only in retrospect.

Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein (2001): A remake of a Tamil romance, this R. Madhavan–Dia Mirza love story was declared a disaster at the box office on release. Critics at the time dismissed it as formulaic, and it barely made a ripple commercially. Yet over the years, RHTDM quietly attained a devoted fan base, especially among youngsters who discovered it on TV and DVD.

It’s now considered a “cult classic 2001 film” that has “earned a special place in the hearts” of the audience. The soundtrack became hugely popular, and the on-screen chemistry turned nostalgic viewers into loyal fans. Remarkably, RHTDM’s second life has sparked talks of a sequel 20 years later. What failed in 2001, for lacking star power or promotion, is today fondly remembered as an era-defining romance.

Swades (2004): Coming off the blockbuster Lagaan, director Ashutosh Gowariker and superstar Shah Rukh Khan made a film diametrically opposed to escapist fare. Swades is a slow-burning drama about an NRI NASA scientist returning to an Indian village to contribute to grassroots development. Its exploration of rural empowerment, brain-drain reversal, and patriotism through social work was unusual in 2004. The film underperformed commercially and had a mixed initial reception. Many fans expecting an entertainment juggernaut were disappointed by its documentary-like pace.

However, Swades has since been “celebrated as a cult classic and … a film ahead of its time”. Critics and audiences now count it among Shah Rukh’s finest, praising its earnest message of nation-building. On the film’s 20th anniversary in 2024, Gowariker reflected on how “Swades continues to resonate with audiences today”, calling its enduring impact “truly humbling”.

What didn’t set the box office on fire in 2004 ended up igniting inspiration in countless real viewers – some reports even mention NGO initiatives and returning NRIs crediting Swades as an influence. Its iconic scene of a village woman selling a glass of water to the hero for 25 paise is now etched in pop culture as a wake-up call to India’s inequalities.

Lakshya (2004): Farhan Akhtar’s sophomore film (after Dil Chahta Hai) took a similarly ahead-of-its-time approach, blending a coming-of-age journey with a war drama. Starring Hrithik Roshan as an aimless young man who finds purpose in the Indian Army, Lakshya won critical appreciation but was labeled a commercial flop upon release. Audiences expecting a typical war movie or a star-driven spectacle didn’t turn up, and the film’s nuanced exploration of self-discovery didn’t initially connect with the masses. Fast-forward to today, and Lakshya is firmly regarded as “Hrithik Roshan’s cult-classic” war film, an inspirational story of finding one’s identity that only grew more popular with time.

Fan comments on its recent anniversary re-release note it “was way ahead of its time… wonder why we don’t see these kinds of movies these days.”. To celebrate 20 years of Lakshya in 2024, the makers even re-released it in cinemas for a new generation. A film once deemed a disappointment has now achieved cult status, with its themes of personal duty and national service resonating more strongly in an era when Bollywood’s war films often veer into jingoism. Lakshya’s subtlety looks visionary in hindsight.

These examples show how mainstream Bollywood experiments in the 2000s often struggled in the moment but later attained classic standing. Whether it was satire on media, realistic youth culture, or patriotism with a social conscience, these films were outliers in their time. Today, thanks to nostalgia and changing audience tastes, they are lauded as trendsetters.

Trailblazers of Indie Cinema in the 2000s

Parallel to the big studios, the 2000s also saw the rise of a bold independent cinema movement. Visionary filmmakers like Anurag Kashyap, Vishal Bhardwaj, Sudhir Mishra, Dibakar Banerjee, Nagesh Kukunoor, and others crafted offbeat films that often faced distribution hurdles and muted audience response. Yet these films won acclaim in niche circles and, in retrospect, have proven incredibly influential. Let’s look at some pioneering indie films of the 2000s that were truly ahead of their time:

Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005): Set against the turbulent 1970s backdrop of the Emergency and Naxalite movement, Sudhir Mishra’s political drama had limited reach during its release. Without a big PR machine, the film opened small and was only a “minor hit” in commercial terms. However, its complex storytelling and strong performances by Kay Kay Menon, Chitrangada Singh, and Shiney Ahuja earned it immense critical praise.

Over the years, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi “garnered widespread love and acclaim”, achieving cult status as a touchstone political film. As Mishra reflected on its 20th anniversary, the film “crossed the test of time”, people still talk about it decades later, and there were even plans for a re-release to introduce it to new viewers. This film’s journey, from semi-obscurity to being widely regarded as one of the best depictions of youthful idealism in tumultuous times, exemplifies how quality cinema eventually finds its audience. Its commentary on revolution, idealism, and heartbreak feels just as relevant now, and it paved the way for later political dramas in Hindi cinema.

You May Also Like to Read

- The OTT Revolution: How Netflix and Amazon Prime Changed Bollywood Storytelling

- The Evolution of Bollywood Lyrics: From Poetic Classics to Viral Hook Lines

Black Friday (2007 release, made in 2004): Anurag Kashyap’s gritty docudrama on the 1993 Bombay bomb blasts had a famously rough journey. The film was ready by 2004 but was banned from release for three years due to ongoing court cases. When Black Friday finally hit theaters in 2007, it got glowing reviews (and international acclaim after a Locarno festival premiere), but its commercial run was limited by the heavy subject matter and lack of star appeal. Yet, with time, Kashyap’s unflinching chronicle has come to be “regarded as one of the finest films of Hindi cinema”, often cited by filmmakers and critics as a benchmark in realistic crime drama.

It’s now firmly a cult classic, admired for calling a spade a spade in an era when such political candor was rare. In fact, Kashyap was doing in 2004 what even today’s filmmakers find daring, using real names of politicians and showing uncomfortable truths on screen. Directors like Danny Boyle drew inspiration from Black Friday (Boyle incorporated a chase sequence homage in Slumdog Millionaire after watching it). Kashyap “broke boundaries” and paid a price then, but today the film’s ahead-of-its-time authenticity is lauded as visionary.

No Smoking (2007): Perhaps one of the most bizarre, avant-garde films Bollywood produced in the 2000s, this Anurag Kashyap creation starring John Abraham blended surreal noir, satire, and horror in a cautionary tale about a chain-smoker. It was a “famous box office disaster”, outright rejected by audiences in 2007 who found its Lynchian storytelling “too difficult to process”. Critics were confounded, and the movie’s failure even drove Kashyap into depression. However, No Smoking has since been rehabilitated as a cult gem. With multiple viewings, cinephiles began unpacking its layers of metaphor, recognizing it as an art piece full of hidden analogies.

Filmfare later noted how the “dark, unfamiliar storyline” and surreal treatment were simply “unpalatable to the audience” then, but would likely find appreciation in a different time. Indeed, today’s viewers (especially on streaming) seek out No Smoking for its unique experience, and it’s studied as an example of Bollywood’s experimental phase. The film’s journey from total rejection to respect (among a niche, at least) underscores how being ahead of one’s time often means initial isolation. Kashyap himself quipped that he doesn’t make movies for the mass audience, but for a “cinema-literate” crowd that discovers films at its own pace, a prediction borne out by No Smoking’s fate.

Khosla Ka Ghosla (2006): In 2006, this delightful comedy about a middle-class Delhi family reclaiming their land from a scheming property dealer earned critical raves for its intelligent humor and realism. Yet, it “wasn’t a commercial success” initially. Made on a modest budget by debutant director Dibakar Banerjee, Khosla Ka Ghosla relied on word-of-mouth. Slowly, it picked up steam and is now widely loved as one of Bollywood’s best satires on the urban middle class. In fact, the film is now considered “Bollywood’s cult classic” that “set the tone for films rooted in reality and humor beyond slapstick”.

Eighteen years later, its lines (“Jaidev ji ki entry karao!”, for instance) are part of pop culture and frequently used as memes. A recent theatrical re-release in 2024 was met with cheers, as a “new generation will experience its magic”. The success of Khosla Ka Ghosla in hindsight proved that Indian audiences do appreciate well-crafted realistic stories; perhaps it just needed time (and the home video circuit) for its gentle wit to find a following. It also launched Dibakar Banerjee’s career, leading to more such genre-bending films (like Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! in 2008) that blended satire with social commentary.

Johnny Gaddaar (2007): Sriram Raghavan’s neo-noir thriller had all the ingredients of a cult classic: a twisty plot inspired by pulp fiction, a retro style homage to 1970s Indian thrillers, and an ensemble of fine actors. At the time of its 2007 release, however, Johnny Gaddaar went largely unnoticed by the mainstream audience. It got mixed reviews and lackluster box office numbers. But as often happens with film noir, it eventually gained popularity with aficionados of the genre. Today, it’s hailed as “a cult classic” of modern Bollywood, admired for its taut screenplay and distinct aesthetic with ’70s references. Contemporary directors and fans frequently cite Johnny Gaddaar as one of Bollywood’s best thrillers.

Its slow-burn success exemplifies how OTT platforms and film clubs in the 2010s helped resurrect movies that were too niche for their theatrical time. Raghavan’s own later triumphs (like Andhadhun) have driven new viewers back to discover his early gem. Once an ignored flop, Johnny Gaddaar now enjoys “must-watch” status among thriller fans, validating its director’s belief in content over star power.

Maqbool (2003): Vishal Bhardwaj’s adaptation of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, set in Mumbai’s gangster milieu, was years ahead in envisioning Bollywood as world-class literature on screen. The film featured powerhouse performances (Irrfan Khan, Tabu, Pankaj Kapur) and won critical acclaim, but it failed to draw audiences used to masala entertainment. Over time, Maqbool has been recognized as a cult classic that launched Bhardwaj’s celebrated trilogy of Shakespearean Indian adaptations. It proved Indian cinema could marry Shakespeare with a desi context, a concept not widely accepted in 2003.

Today, Maqbool is studied in film courses and appreciated for its craft, underscoring how its initial box office evasion eventually gave way to a lineage of followers, elevating it to cult status (much like classics of earlier decades did).

My Brother… Nikhil (2005): Onir’s low-budget drama about a gay athlete diagnosed with HIV in Goa was a path-breaker in terms of theme. In 2005, homosexuality was still a taboo topic in India (Section 377 was in force), and films rarely depicted LGBTQ lives sensitively. This film received critical acclaim and even a U (unrestricted) certificate from censors for its dignified storytelling, but it struggled to find a wide audience then. With changing times, My Brother… Nikhil is now acknowledged as “truly way ahead of its time” for treating homosexuality sensitively, minus ugly jokes or shock value.

It portrayed a same-sex relationship and AIDS stigma with normalcy and empathy, long before mainstream Hindi cinema dared to. Today, the film is often hailed during Pride Month and cited as an important milestone in queer representation. Director Onir, now a vocal LGBTQ activist, notes the irony that people celebrate the film now while it had a limited run then.

The movie’s belated appreciation reflects India’s evolving social consciousness. Young viewers who see it on streaming find it remarkably progressive for 2005, and many say it made them feel “seen” on screen. In short, My Brother Nikhil opened a conversation that the country caught up with a decade later, a classic example of a film way ahead of its era.

The above films are just a few highlights. The 2000s indie wave also gave us Dor (2006), a poignant tale of female friendship and forgiveness in patriarchal Rajasthan, Manorama Six Feet Under (2007), an underrated neo-noir mystery now admired for its clever homage to Chinatown, and Love Sex aur Dhokha (2010), technically just outside the 2000s, but conceived in that decade as India’s first found-footage anthology on voyeurism (a trend that exploded later with reality TV and viral videos). Each of these films initially catered to a niche, but their influence is seen in the more experimental, bold Hindi cinema of the 2010s and beyond.

It’s worth noting how streaming platforms and film festivals in later years played a crucial role in “rediscovering” these indie trailblazers. With the rise of OTT, viewers could find and appreciate these titles on their own terms, free from the Friday box office frenzy. For example, Kashyap has mentioned that his audience “has things to do” and watches at their own pace, which became true in the streaming era, where films like No Smoking or Black Friday found new life. This trend has only solidified the cult reputations of these movies.

Regional Cinema Mirrors and Influences

Hindi cinema doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Often, trends in Bollywood have parallels in regional industries, and the 2000s were no exception. Several regional films from the decade, though rooted in local cultures, mirrored the experimental spirit and even influenced Bollywood narratives later on.

Tamil Cinema’s Bold Experiments: Tamil films in the early 2000s, especially those involving veteran actor-filmmaker Kamal Haasan, were pushing envelopes much like Hindi indies. Anbe Sivam (2003) is a prime example. This road drama, starring Kamal Haasan and R. Madhavan, tackled themes of humanism, socialism vs capitalism, and religious unity through the story of two mismatched travelers. It flopped commercially during its Pongal 2003 release, clashing with masala fare. But with time, Anbe Sivam turned into “a cult classic in many ways”, regarded today as one of Tamil cinema’s finest works.

It was arguably “way ahead of its time”, as actress Khushbu (whose husband Sundar C directed it) noted, the film “crashed at the box office and attained a cult status later”, and “was way ahead of its time” in its messaging. Fans only truly appreciated its depth years later, with special screenings now drawing full houses of enthusiasts. Interestingly, one scene in Anbe Sivam has Kamal’s character mention the word “tsunami”, a year before the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami tragedy, a coincidence that fans often cite as proof of the film’s uncanny foresight! Kamal Haasan’s Hey Ram (2000) is another case.

This trilingual period film (made in Tamil and Hindi) explored an alternate history surrounding Mahatma Gandhi’s assassination, communal violence, and personal vengeance. It faced protests and political backlash on release, and its complex, non-linear narrative left audiences divided. Yet Hey Ram won 3 National Awards and over the last 25 years has been reassessed as a “cult classic masterpiece” of Indian cinema. Despite being a period drama, it was “progressive and modern in its ways”, daring to critique communalism long before such themes were common in mainstream film.

History has been kind to Hey Ram; directors like Quentin Tarantino have even acknowledged inspiration from Kamal’s ambitious ideas (Kamal’s Abhay inspired a Kill Bill animation sequence, per his interviews). Bollywood’s own attempts at partition narratives in later years (Pinjar, 1947 Earth) gained from the path Hey Ram blazed in blending fact and fiction so boldly. Furthermore, Tamil hits often found delayed success in Hindi either via remakes or influence.

Shankar’s Mudhalvan (1999), as mentioned, became Nayak in 2001, and while Bollywood fumbled with it then, the idea of the righteous common man leader gained traction in later Hindi cinema (echoes seen in films like A Wednesday (2008) where a “common man” shakes the system). Likewise, the vigilante psychological thriller Anniyan (Aparichit) (2005) was too “out there” for some, but its Hindi dubbed version found cult love on TV, and its theme of split-personality justice was an inspiration for later anti-hero films.

Bengali and Malayalam Parallels: In West Bengal, the early 2000s saw auteurs like Rituparno Ghosh and Buddhadeb Dasgupta making waves. While their works were critically acclaimed at the time (and thus not “misunderstood”), the crossover influence on Bollywood was limited. However, one can argue that the introspective, personal storytelling they championed seeped into the sensibilities of Hindi filmmakers over time. For example, the nuanced portrayal of relationships in films like Raincoat (2004, Bengali director in Hindi) didn’t succeed then but is appreciated now, akin to the fate of some Hindi indies we discussed.

Malayalam cinema in the 2000s was in a transitional phase, but interestingly, its New Wave would erupt in the early 2010s with filmmakers who grew up on precisely the kind of 2000s cult films we’ve mentioned. Directors in Kerala and even in Marathi cinema often cite films like Dil Chahta Hai or Black Friday as influential in showing new storytelling techniques beyond formula.

Influence of Regional Hits on Late-2000s Bollywood: By the end of the decade, Bollywood started learning from South industries in another way, via remakes. The trend of remaking successful Telugu/Tamil films into Hindi blockbusters began around 2008-09. For instance, Aamir Khan’s Ghajini (2008) was a remake of a 2005 Tamil film of the same name. The Tamil Ghajini itself was a slick thriller that some might say drew from Memento; it was a smash in Tamil, and its Hindi version became the first Bollywood film to cross ₹100 crore, validating that audiences had warmed up to high-concept thrillers by decade’s end.

Similarly, Salman Khan’s 2009 hit Wanted was a remake of Telugu Pokiri (2006). One could argue that Bollywood’s mainstream renaissance of action in the late 2000s (leading into the 2010s action-entertainers) was directly influenced by regional cinema that had already been delivering such content. Thus, a film like Pokiri was ahead of its time for Bollywood; when it came in Hindi as Wanted, it sparked a new trend.

In summary, the exchange was two-way: some regional films faced the same fate of being ahead of their time (and later appreciated) in their own milieu, and some were ahead in relation to Hindi cinema, eventually pulling Bollywood forward. The 2000s across India were fertile with experiments, many planted seeds that only bore fruit in the subsequent decade.

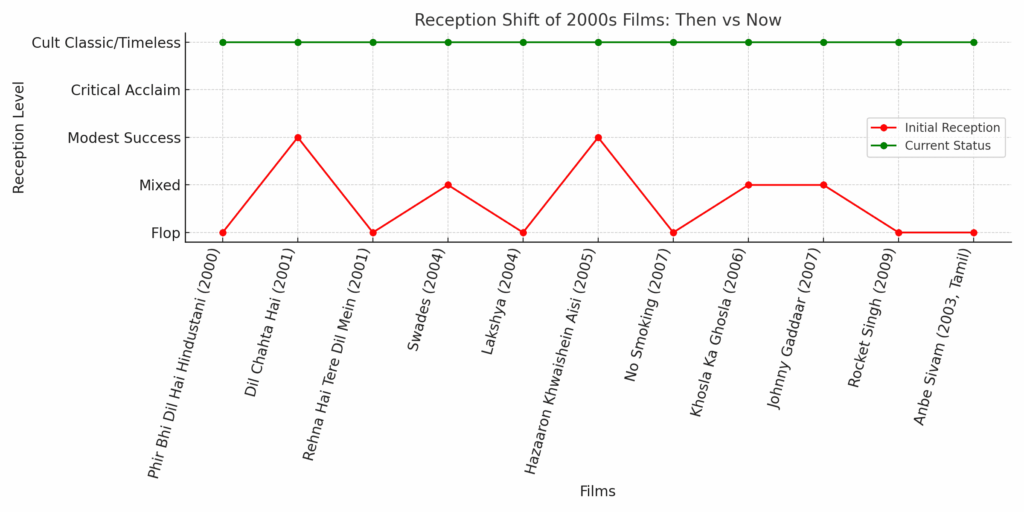

Then vs Now: Reception Comparison

Nothing illustrates the journey of these films better than a direct comparison of how they were received at release versus how they are seen today. Below is a snapshot of a few key titles from the 2000s, showing “Then vs Now”:

| Film (Year) | Initial Reception (Then) | Current Status (Now) |

|---|---|---|

| Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani (2000) | Flop at the box office; audience didn’t accept its media-politics satire; described as a “disaster” by its star. Critics were mixed, expecting a rom-com instead of a dark comedy. | Cult classic for its prophetic take on TV news wars and political scapegoating. Seen as ahead-of-time satire, now appreciated in light of today’s media climate. Often rewatched and discussed on social media. |

| Dil Chahta Hai (2001) | Moderate success (not a blockbuster); youth loved the fresh narrative, but older audiences found it too casual. Critics praised it, but it didn’t win major awards except a National Award for Best Hindi Film. | A timeless classic that defined millennial friendship in Bollywood. Revered by young and old alike, spawned a genre of buddy films. Frequently listed among Bollywood’s best, with fans still quoting its dialogues. Its influence on subsequent filmmakers is widely acknowledged. |

| Rehna Hai Tere Dil Mein (2001) | Commercial failure (announced a disaster); minimal buzz on release. Dismissed as another routine romance, overshadowed by bigger films. | Cult romantic favorite with a dedicated fanbase. The music and innocence won hearts over time. Now regarded with nostalgia as one of the sweetest love stories of its era. A sequel is in demand due to its enduring popularity. |

| Swades (2004) | Below the expectation box office, seen as too slow and intellectual for mass appeal. Despite some critical acclaim, it was deemed a disappointment compared to the director’s previous hit. | Celebrated as ahead of its time, often called one of Shah Rukh Khan’s finest films. Has a cult following and is cited for inspiring real social change. Widely re-appraised by critics and audiences as a modern classic with a meaningful message. |

| Lakshya (2004) | Flop initially, despite critical appreciation. Audiences expecting a war action film were taken aback by its character-driven story; it didn’t fare well commercially. | Cult status has been achieved over the years. Now seen as a rousing coming-of-age war drama. On its 20th anniversary, re-released to fanfare. Viewers applaud its inspiring theme and note it “was way ahead of its time” in 2004. |

| Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi (2005) | Limited release; modest earnings (semi-hit). Strong critical praise but low awareness among the public in 2005. | Cult political film is widely acclaimed in hindsight. Its reputation grew via word-of-mouth and home media. Now studied as a landmark depiction of 1970s political idealism. Still remembered and talked about even 20 years later. |

| No Smoking (2007) | Disaster at the box office; panned or perplexed by most critics. Viewers found it “boring” or incomprehensible, and it lost money, pushing the director into despair. | Cult favorite among cinephiles and art-film enthusiasts. Seen as a bold, avant-garde experiment that offers new meanings on repeat viewings. Often included in lists of Bollywood’s great cult movies. Its once “unfamiliar” style is now appreciated for breaking cinematic ground. |

| Khosla Ka Ghosla (2006) | Underperformed in theaters (despite critical acclaim for its script). Many missed it due to low-key marketing. | Beloved cult comedy that is “still loved by audiences even after 18 years”. Recognized as a breakthrough film that heralded a wave of realistic slice-of-life comedies. Enjoys frequent TV reruns; lines and characters have become iconic (and meme-famous). Re-released in theaters to celebrate its legacy. |

| Johnny Gaddaar (2007) | Went unnoticed by the masses; only received a lukewarm response in 2007. Fans of noir were a small group then. | Neo-noir cult classic now, often recommended as a must-watch thriller. Earned critical re-evaluation and fan following for its stylish narrative. Seen as a trendsetter for modern thrillers in Bollywood, regularly featured in “underrated gems” lists. |

| Rocket Singh: Salesman of the Year (2009) | Flop at release; audiences were more into masala fare and didn’t connect with its subtle take on office life. It was ahead of the curve on India’s startup culture theme. | Cult hit among millennials, especially professionals. Hailed as “years ahead of its time” for critiquing corporate culture just after the 2008 recession. Now appreciated for its honest portrayal of workplace ethics. Has gained popularity via streaming, and its relevance has grown with India’s startup boom. |

| Anbe Sivam (2003, Tamil) | Flop in Tamil Nadu; viewers in 2003 didn’t flock to this offbeat road movie amid commercial releases. Critically praised but lacked an initial audience. | Cult classic of Tamil cinema, revered for its humanist message and bold storytelling. Today, it’s celebrated as a “timeless classic” and one of Kamal Haasan’s best, with fans across India. Its failure is now seen as a marketing issue of its time, the film itself is considered a masterpiece that “the audience failed to celebrate then”. |

Table: A comparison of select 2000s films, their reception at the time of release versus their status now (2020s). Many initially flopped or faced mixed reviews, but later attained cult classic stature and critical respect. Sources include box office reports and contemporary critiques for “Then”, and recent commentary, re-release reports, and critical reappraisals for “Now”.

As the table shows, perception can dramatically change with time. A movie too experimental or offbeat for its release year might be perfectly palatable a decade later, when audiences have evolved or when real events make its themes more relevant. For instance, the media circus depicted in Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani felt over-the-top in 2000 but seems spot-on in the age of TRP-driven news debates. Rocket Singh’s honest salesman was a misfit in 2009’s cinema, but in today’s startup culture, many find him relatable. And Swades, undervalued during the shine of glossy NRI films, anticipated the coming discourse on brain drain, reverse migration, and rural development that is now mainstream.

Legacy and Current Relevance

In recent years, the industry and cinephiles have officially begun honoring these once-forgotten films. We see this in multiple ways:

Anniversary Celebrations & Re-Releases: As these films turn 15 or 20 years old, there’s a wave of nostalgia-driven events. In 2022, Anbe Sivam had special fan screenings in Chennai, where audiences who were kids in 2003 got to watch it on the big screen, a testament to its enduring appeal. In 2024, Lakshya and Khosla Ka Ghosla both saw re-releases to commemorate two decades, with their directors and cast reminiscing on social media about how those films initially struggled but ultimately prevailed.

Ashutosh Gowariker penned a heartfelt note on Swades’ 20th anniversary, expressing gratitude that the film “continues to resonate” and is discussed with such passion today. Such occasions often spark media articles and retrospectives, further cementing the films’ classic status.

Streaming and Social Media Virality: Many of these movies found their second life on television and now on streaming platforms. OTT services have made Dil Chahta Hai, Swades, Hazaaron Khwaishein Aisi, etc., easily accessible to young viewers who weren’t around for their theatrical run. As a result, social media is abuzz with fresh takes, think Reddit discussions titled “Just watched RHTDM for the first time, wow!” or Twitter threads analyzing No Smoking’s ending.

Memes and GIFs from these films circulate widely: e.g., the comedic frustration of Anupam Kher’s character in Khosla Ka Ghosla is now a popular reaction meme, and dialogues like “Dhondu, just chill” (Johnny Gaddaar) or “Mohan Bhargava reporting from NASA” (Swades) are quoted for fun. This online chatter not only keeps the films alive, it introduces them to new audiences globally, enhancing their cult stature.

Critical Reappraisal & Academic Interest: The passage of time has also led critics and scholars to reassess these works. Reputed publications now run features like “20 Years of Monsoon Wedding: A Timeless Classic” and “Films That Aged Well from the 2000s”. For instance, Film Companion published “A Film Ahead Of Its Time: Monsoon Wedding,” highlighting how Mira Nair’s 2001 film dared to address child sexual abuse and female desire under the garb of a family drama, something mainstream filmmakers “didn’t dare to” do back then.

The piece notes the film’s “significant contribution” to later dysfunctional family dramas and how its progressive elements are lauded today. Similarly, Sudhir Mishra’s Hazaaron… is frequently dissected in film studies for its narrative and political nuance. Universities and film schools include several of these once-flops in their curriculum to illustrate concepts of narrative innovation, genre subversion, and socio-political commentary in cinema.

Influence on New Filmmaking Trends: The delayed success of these 2000s films paved the way for the content boom of the 2010s. The fact that Dil Chahta Hai and Lakshya eventually got their due gave confidence to studios to back films like Zindagi Na Milegi Dobara or Rang De Basanti (which, although successful, were following the path blazed by DCH’s urban cool and Lakshya’s earnest patriotism).

Anurag Kashyap’s cult filmography in the 2000s directly enabled the emergence of the “indie film” market in Bollywood, by the time he made Dev.D in 2009, audiences were more receptive, and that film (a wild modern take on Devdas) became a hit, something unlikely without the learnings from his earlier cult efforts. Dev.D itself is a case: it might have been rejected had it arrived in 2005, but by 2009 the urban multiplex crowd was ready for its experimental style, thanks in part to the baby steps taken by movies like No Smoking and Ek Hasina Thi.

And the success of Khosla Ka Ghosla on DVD gave producers faith in Dibakar Banerjee, who then made Oye Lucky! Lucky Oye! (2008) and Love Sex aur Dhokha (2010) further push cinematic boundaries.

Finally, it’s heartening to note that the creators of these films are finally being vindicated. As veteran filmmaker Mahesh Bhatt once said, “Films are like wine, some turn sour, but some get better with time.” The 2000s gave Bollywood a robust cellar of such wines, movies that needed a few years (or a couple of decades) for the world to acquire their taste. From being forgotten or ridiculed, these films have become reference points for quality and courage in filmmaking.

Bollywood’s forgotten decade is forgotten no more, it’s being celebrated as a time when courageous storytellers were ahead of the curve. The legacy of these 2000s cult classics lies not only in the cult followings they now command but in how they expanded the possibilities of Indian cinema. They remind us that a film’s true impact might be known only in hindsight, and that great art can transcend its era, waiting patiently for the audience to catch up. As viewers in 2025, we’re lucky to reap the rewards of those creative gambles taken years ago, and it’s our responsibility to keep their flame alive for future generations of film lovers.